Showgirls: A Defense

In which I attempt to do the Impossible

Paul VerHoeven and Joe Ezterhas’ Showgirls has been universally panned as one of the worst movies ever made—an exploitative, misogynistic film with an incomprehensible plot and abysmal acting. Professional critics agree. Giving it the lowest score possible, the LA Times’ Kenneth Turan says

Lacking the combustible Sharon Stone and Michael Douglas in leading roles [Ezterhas’ previous film was Basic Instinct], Showgirls descends into incoherent tedium. Though the filmmakers’ incessant talk about vision, artistry and honest self-expression lead one to expect a sexually explicit biopic about the Dalai Lama, what is in fact provided is depressing and disappointing as well as dehumanizing.

Writing for the Austin Chronicle Marjorie Baumgarten says

The story is so shabbily built that it can make no valid claim to motives other than the filmmakers’ mercenary desires to cash in on the public’s prurient interests. And even on this bottom-feeder level, Showgirls fails to deliver the goods.

She, too, gave the film the lowest score possible.

Even more generous critics, like USA Today’s Susan Wloszczyna stop short of praising the film, asking (rhetorically) “Who knew such a seamy swim in the misogynistic swill of life could be so entertaining?”

In short, the best that could be said about the film seems to be that it can be fun, but only if one ignores or embraces its crude sexuality, misogyny, and over-the-top acting. And that’s a tall order given how omnipresent each of these elements is in the film. It seems that even with herculean efforts, the payoff for watching it are minimal.

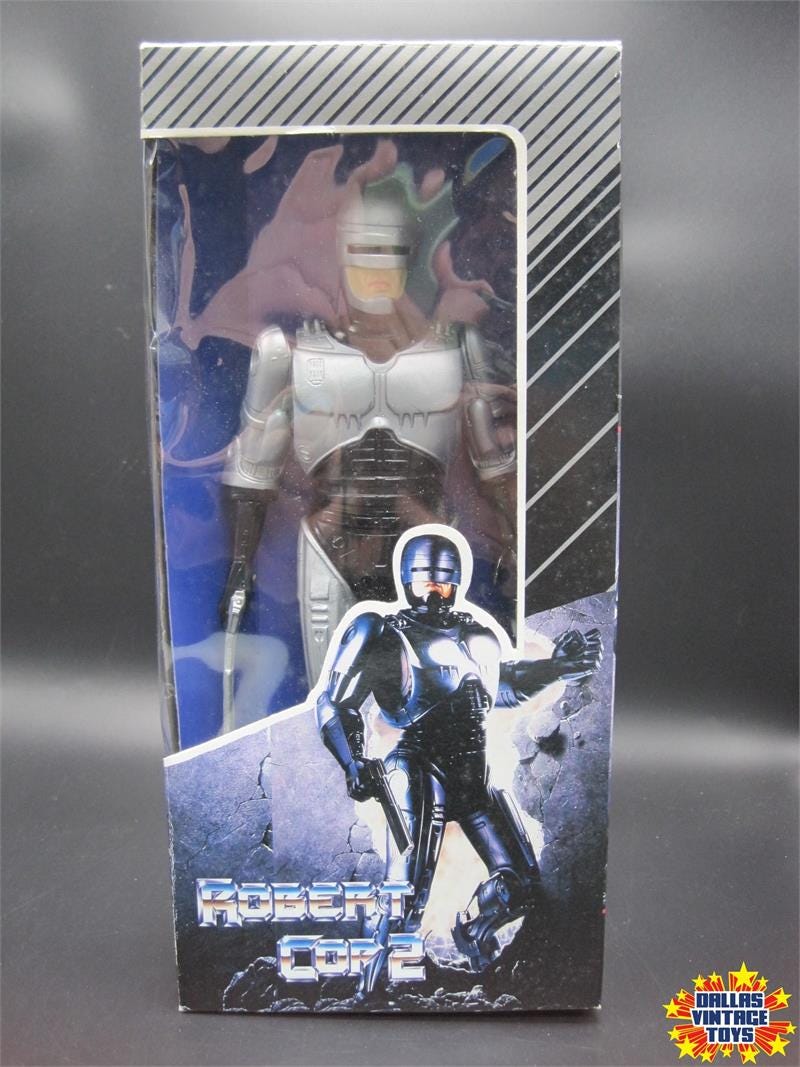

Yet, as a big fan of Verhoeven’s other films (Starship Troopers and Robocop rank as some of my favorite movies of all time), I find the claim that Showgirls is an exception to be rather odd. How could Verhoeven make such brilliant satires and such an incomprehensibly bad film? The matter is further complicated by the fact that although they’ve now come to be appreciated for their brilliance, both Starship Troopers and Robocop were deeply misunderstood when they came out and maligned as shallow, ultraviolent, and badly written. Is it possible that, like those films, Showgirls has been misunderstood by its audience?

In short, I believe the answer is yes. In what follows I try to make the case briefly by offering a key through which we can read the film that not only explains why it’s so weird, but that also shows why it’s worth a re-watch.

[Content warning: this post discusses sexual themes including sexual violence. I do not recommend watching the movie if either of these themes is a trigger for you]

Let’s begin with the fact mentioned earlier that virtually all of Verhoeven’s movies are satires. Moreover, they are subtle Juvenalian satires that don’t wear their satirical target on their sleeves. They are not presented nor advertised as such but rather as glossy, Hollywood genre movies. Starship Troopers doesn’t claim to be anything other than a military space adventure, and Robocop doesn’t claim to be anything other than a sci-fi cop action film. The initial allure of these films is not the fact that they’re satires, but the promise that you’re going to be watching a certain kind of movie the outlines of which you’re already familiar with. One goes to see Starship Troopers wanting to see Space Marines shoot up a bunch of alien bugs because one has already seen Aliens; one goes to see Robocop wanting to see street justice delivered to criminals because one has already seen Dirty Harry and Deathwish. As such, both movies also lean heavily on the tropes of those genres and hitting the beats that are expected of those genres. On the surface, Robocop plays out as a revenge/redemption story of a good cop fighting against comically ruthless criminals. Likewise, Starship Troopers plays out as a coming-of-age story about sacrifice and friendship.

Yet, something odd happens in each of these films that critics are quick to notice: things feel off. The action scenes don’t have the same thrill that normal genre movies have, the emotional scenes feel awkward, the sex scenes are decisively unsexy (think of the shower scene in Starship Troopers or the first time Rico and Flores have sex with the blessing of their commanding officer). One leaves both films somehow dissatisfied or put-off. It’s true, the Roughnecks survive to fight another day and Murphy takes down the drug dealers, but despite the fact that all the beats have been hit, there’s a feeling of emptiness that lingers with the viewer that makes them feel like something along the way didn’t quite go right.

What “doesn’t go right” is the ideology that serves as the backdrop of the film and which serves to structure and make sense of the actions of the characters. In Robocop we are presented with a cop film in which the dominant ideology is that of neo-liberal privatization cracked up to the max. Consider just some of the elements of the film that support this: a gutting of a public service (police) that has to be buttressed by private corporations that claim they will solve a social problem through the introduction of special high-tech interventions; the fact that crime has to be reduced in Detroit not so that people can live better lives, but because one of the corporations needs the slums cleared out to make living space for its employees; the literal fusion of man and machine for the sake of efficiency, etc.

In Starship Troopers we are presented with a fascist ideology in which service to the nation is literally paid with blood (and lost limbs, and missing eyes, and so on) by young people in order to achieve some measure of success—if one is going to do anything important one has to first serve in the military to become a citizen, after all. Furthermore, the goal of this service is nothing other than perpetual consumption and expansion since we are repeatedly told that the bug planet is on the other side of the galaxy, that it’s completely desolate and hostile, but that it nevertheless must be conquered.

Each of these films deserves its own in-depth discussion, but it’s enough to say here that understanding this allows us to better see the kind of movies each is. Namely, they are genre movies, but they are the kinds of genre movies that specific ideologies would make. Thus, Robocop is the kind of cop movie that a neo-liberal ideology taken to its limits would make and Starship Troopers is the kind of space adventure that a fascist regime would make. This can often be missed because the ideology in the film isn’t flagged explicitly (although there’s a case to be made that Neil Patrick Harris’ uniform at the end of Starship Troopers is a pretty massive flag!). Rather, the ideology works in the background. Nobody says “Dammit, we are neo-liberals and we use the police as the enforcement arm of capital to clear the way for new ventures! That’s why we need Robocop!” or “As good fascists who want to keep a pure nation based on blood, sacrifice, we must always keep the fires of war going! That’s why we need to invade the bug planet on the other side of the galaxy!” And it would be bizarre if they did because ideology always inhabits that unspoken space that serves as the starting point from which we make our decisions. After all, “regular” movies don’t do this with the kind of ideology that is operating in the background either since to do this would, in most cases, completely unnecessary—we already share the assumptions of the kind of world the filmmaker wants us to inhabit so it’s not necessary to point them out.

When we encounter Verhoeven’s works we experience a kind of ideological doubling, amplified by the fact that the films still follow the regular beats of the genre they’re a part of. It’s this doubling that makes the sex unsexy, the violence arbitrary and extreme, and the acting wooden. It all feels unnatural because the starting assumptions that would make the actions and motivations of the characters feel natural are slightly off-kilter. Most film critics notice the imbalance this produces, but, at least initially, they fail to get to its source and attribute the discomfort that it produces as the result of bad acting, bad writing, or bad directing.

What does this have to do with Showgirls? The suggestion is a simple one: if all of Verhoeven’s movies have the same aim and same structure, the it’s reasonable to assume that something similar is going on with that film as well.

The two relevant question then become: first, what kind of genre movie is Showgirls, and, more importantly, from what ideological standpoint is the film being made? Or, to put it more concretely: what kind of ideology would make Showgirls?

The answer to the first question is, I believe rather straightforward: it is a movie about self-discovery, disillusionment, and female empowerment. It is, at the same time, presented and advertised as a sexual movie. Thus, it hooks people in with the promise of hyper-sexuality with the thin veneer of a morality play.

The bare-bones of the story is a familiar one: girl sets out on an adventure to fulfil her dreams, encounters immediate setbacks but continues to believe that her dream is achievable, works through many moral and emotional challenges to get to the top, realizes that her dream was never what she thought it would be, and abandons it on her own terms, starting the cycle again having grown for the experience. On top of this basic structure is added the layer of sexuality because what Nomi, the main character, does for a living is, of course, hook, strip, and dance.

Far from incomprehensible, as critics claim it is, the plot is simple and derivative. All the beats that one would expect of such a movie are clearly telegraphed—you could figure out the plot without paying too much attention to the film.

What makes it such a weird film, however, is all the other things that are the result of the particular ideology working in the background. Consider, for example, a short list: Elizabeth Berkley’s (Nomi’s) over-the-top acting, the aggressive and violent ‘dance’ numbers, the child-like friendship with the seamstress friend, the sexual tension with Gena Gershon’s character, the inhuman sex scene in the pool, the matronly stripper who makes misogynistic jokes, the dancer love interest who gives up on dancing to work at a grocery store with his new wife, the brutal sexual violence, the fact that there’s so much nudity and, yet, none of it feels even remotely erotic, etc. The list goes on and on.

If these bizarre elements are, as I’ve argued, the result of the kind of ideological doubling that is present in Verhoeven’s other films, then we can return to the second question raised earlier: from what ideological perspective do these elements make sense—who is this hero’s journey made by and for?

The answer, I believe, is simpler than expected: Showgirls is a female-empowerment movie made entirely in the misogynist ideology. It presents and shows women, their concerns, their struggles, hopes and dreams from the perspective of men who neither understand nor care to understand women.

Consider how this helps us understand some of the items listed above. Why is Elizabeth Berkley so volatile (it’s worth noting that Verhoeven told her to act this way)? Because from the ideological perspective this is how women who have aspirations act! They’re always emotional and their emotions are either always the result of some naive caprice, or they’re weapons to be used against other women with whom they compete. In the misogynist framework women can’t act otherwise.

Why are her “sex scenes” equally violent and bizarre? Because from the misogynist ideological standpoint, that’s what sex is. It’s violent, aggressive, explicit, and fast. Nomi doesn’t have sex with Zack—she literally fucks him, writhing and flopping, until he comes. This is the male version of sex taken to its limit, and acted out in a woman’s body. One can almost imagine a room full of misogynists being asked to write a sex scene in which “a woman fucks really good.” Would it look any different from what we see?

Consider, also, the roles that women play. All the women we see are either strippers, hookers, dancers, or work with nails or as seamstresses (as Nomi’s friend Molly does, comically “repairing g-strings;” who would go to a seamstress for a thong?!). In short, women are either presented as saddled with virginal domestic work, or engaged in lewd sexual work that rangers from the low-class stripping to the high class dancing. This is simply what women do for the misogynist: if they have dreams, they have dreams of showing their breasts while part of a big show (where everyone will be paying attention to them); if they don’t have dreams, they show either sell their sexuality in other ways or they do typical women’s work in support of that sex work. And if they happen to get old and are somehow still alive, then they become a matronly parody of sexuality whose role is to draw attention to the “uselessness” of women once they’re past their sexual peak (Here is an example of her ‘excellent’ humor: “You know what they call that useless piece of skin around a twat? [pause] A woman!” The crowd in the club loves the joke). There is no camaraderie between the women in the film: they’re either shallow friends like Nomi and Molly whose interactions are childish and trivial, or they’re potential competitors who must be eliminated on the way to the top.

Likewise, the men in the movie fall into two categories: in the first category are Zack (Kyle McLachlan’s character) , his friends in the casino, and the rapist musician Andrew Carver; and in the second category are the dancer James and the strip-club-owner-with-a-heart-of-gold, Al. The former make money and exploit women, while the latter exploit women, but do so less successfully, and usually can be seen as having some element of morality to them which aims to make them at least a little more sympathetic to the audience. In any case, there are no male characters for whom the exploitation of women—whether it’s purely financial exploitation (ala Al), purely sexual exploitation (ala James), or both (ala Zack)—isn’t part of the general worldview.

Finally, there’s the climax of the movie and it’s supposed “resolution.” What does this amount to? The climax occurs following Molly’s brutal gang rape by the celebrity Andrew Carver and his friends. The rape leaves Molly severely hurt in the same hospital where Cristal (Gina Gershon’s character and Nomi’s main rival) is also recovering from Nomi pushing her down the stairs. Nomi wants to get justice for Molly, but is stopped by Zack who is going to bribe Molly to stay quiet and who blackmails Nomi from going to the police by telling her that he knows about her past. Taking revenge into her own hands, Nomi visits Andrew Carver and brutally beats him. She then visits the two hospitalized women, first to tell Molly that justice has been achieved, and second, to apologize to Cristal for breaking her leg. All is forgiven and Nomi leaves Las Vegas for Los Angeles.

This amounts to another set of strange events that leaves us in the kind of ideological doubling I mentioned earlier. Anyone paying any attention to the film will notice that the resolution is entirely unsatisfying. Justice is decisively not served at the end because nothing fundamentally changes. Zack will continue to do what he has been doing his whole life, Andrew Carver will continue to rape women and will retain his prestigious position with Zack’s help, Molly will still be permanently traumatized by her rape, and Cristal will survive only because the money that she’ll get from the settlement will allow her to (i.e. she continues to survive through her brutalization). In the end, the cycle will continue with new Nomis, new Cristals, and new Mollys and the message is that the only way to escape it is to literally leave and go somewhere else. This is, again, no kind of justice and no resolution for us, the viewers.

But it’s important to note that this is justice from the viewpoint of the misogynist ideologue! A powerful man brutally rapes an innocent woman. Even the ideologue must admit that this is a bad look and they have to address it, so justice takes the form of individual retribution. Nomi’s revenge looks like justice from that perspective because it presents itself as an eye-for-an-eye retribution: the bad guy did something bad (but he didn’t kill anyone!) so something bad must happen to him (without killing him!). From that viewpoint, the Molly and Andrew Carver are square. Similarly, Nomi and Cristal are even in the end, too, because they both see each other as having played the same game—there’s no bad blood between them because they encountered each other as equals and knew the risks and rewards involved. Nomi wins and Cristal loses, but those are just how individual competition works between two people who want something very bad (and really, things aren’t that bad because Cristal gets some money in the end!). Finally, there’s justice for Nomi because, like all coming of age stories, she comes to realize something about herself, what she can do, and what she doesn’t want to be a part of. She is the ultimate winner because she has conquered Las Vegas and has left its seedy life behind.

To be clear, the previous paragraph is how the movie is supposed to make sense on its own ideological terms and not how it appears to us. The way it appears to us, again, is as disappointing, hollow, depressing. It is the same way that the endings of Starship Troopers and Robocop make us feel, too. This is because, if we’re attentive viewers, we realize that the wrongs that are in play that set the events of the film in motion are not simply the individual acts of the characters, but, crucially, the ideological suppositions that make up the background of the film.

For us to feel that there’s a resolution and some kind of semblance of justice at the end of the film we would have to see the entire misogynist framework begin to crumble or come apart. We want to see Andrew Carver not just beaten, but killed, the full force of the law brought against him and men like him and Zack. We want to see Molly recover and find a way to live a happy life. We want Cristal and Nomi to realize that they’re not equal competitors in a game whose rules they know, satisfied at the results of good brinksmanship, but that they’re players in a game whose rules are set against them and designed to exploit them. We want Nomi to continue her passion for dancing in a setting in which she doesn’t have to sell herself.

All of these things are clear to us, but none of them are things that a movie that takes the misogynist viewpoint can do because to do that would be to undermine the very framework that serves to make sense of the world it has created. Showgirls can no more do this than, say, Olympus Has Fallen can serve as a Communist critique of the American Empire. The crucial thing is that whereas the latter kind of film weaves its propaganda by assuming an ideology that it is unaware of, Verhoeven’s movies purposefully assume an ideology and take it to its extreme.

Where does this leave us with a final judgment on Showgirls? Is it not a misogynist film? Is its acting not horrible? Are all the bizarre things mentioned earlier still not in the film?

All that is true, and I think it’s absolutely fair to say that it’s a misogynist film. However, I think it’s also important that it’s a satire of a misogynist film in the same way Robocop is a satire of a neo-liberal film and Starship Troopers is a satire of a fascist film.

Is a satire of a fascist movie that can effectively function as a fascist movie any different from just making a fascist movie? Is a satire of misogyny that can effectively serve as misogyny any different from just plain old misogyny? This is a difficult question, but I want to offer a tentative yes. The difference, I believe, is to be found precisely in those places where the difference between the movie’s ideology and our general ideology (whatever mix of crap that might be) come in tension. Verhoeven’s movies differ from non-satirical fascism, neo-liberalism, or misogyny precisely because they show us how terrible and inhuman these ideologies when made consistent are. This is what makes them so strange and off-putting in so many ways. In that respect I’m less worried that these films serve as ways of showing a consistent and coherent fascism/neo-liberalism/misogyny that leaves us entertained but uncomfortable, and much more worried about the day when we stop being uncomfortable. The day in which Starship Troopers is seen as a good movie not because of its satirical value, but because it captures what we believe is the day that worries me. Likewise, the day in which Showgirls is seen as a good movie through and through is one that I wouldn’t like to see.

That being said, the movie really is so strange and so off-putting that I don’t blame anyone for not wanting to watch it.