Socialist Reading Series I: The State and Revolution [Part 4]

Strap yourselves in, cause this is a long one!

Chapter IV: Continuation. Supplementary Explanations by Engels

As the title states, this chapter is about the elucidation of Marx's thoughts by Engels.

The Housing Question

Summary

Engels' suggestion of how people are to be housed after the revolution is fairly straightforward. First, he stresses that there is no real "shortage" of housing and that there is, in fact, plenty of housing available for anyone who needs it if only the space is used rationally. That is, if some people didn't own more housing than they needed and if that housing was made available to those who need it there would be no housing problem. The means by which this rational allocation is to take place are the same as before the revolution: expropriation and billeting. In other words, just as the state can now expropriate private property from certain owners and use it to quarter people (soldiers) therein, so the proletarian state, too, will expropriate living space from owners and billet the homeless and the workers who need a place to live. This cannot be done by the existing state, but must be taken upon by the entire working people.

Crucially, this method of expropriation differ from the Proudhonist/anarchist kind "redemption" insofar as in the latter case the individual who is given some property "becomes the owner of the dwelling, the peasant farm, the instruments of labor" (Lenin quoting Engels pg. 69). By contrast, under Marxist expropriation the collective proletariat who takes control of housing, land, or the means of production retains proprietorship of what it has taken control. Thus, a family might live in an expropriated apartment, but it does not own the apartment by virtue of occupying it--the apartment remains, ultimately, as a property of the people. In other words, the occupants of state provided housing act as renters of a space and the state (i.e. the proletariat mass that has taken control) acts as landlord.

Interestingly, Engels acknowledges this:

Under [Marxist expropriation] the 'working people' remain the collective owners of the houses, factories and instruments of labour, and will hardly permit their use, at least during a transitional period, by individuals or associations without compensation for the cost. Just as the abolition of property in land is not the abolition of ground rent by its transfer, although in a modified form, to society. The actual seizure of all the instruments of labour by the working people, therefore, does not at all exclude the retention of the rent relation.

Lenin quoting Engels, The State and Revolution pg. 69

Lenin doesn't seem to be bothered by the fact that this plan is tantamount to the state becoming a landlord to the dispossessed and requiring rent from them. However, he does use it to highlight the fact that in order to provide housing to individuals there must be some standard of allotment and that "all this calls for a certain form of state, but it does not at all call for a special military and bureaucratic apparatus, with officials occupying especially privileged positions. The transition to a state of affairs when it will be possible to supply dwelling rent-free is connected with the complete 'withering away' of the state." (pg. 69-70)

Furthermore, one of the main lessons that Lenin draws here is that, once again, neither Marx nor Lenin were anarchists. They do not advocate for the immediate abolition of the state overnight, but, as we've seen before, for a preservation of a smashed state under the dictatorship of the proletariat which then withers away.

Analysis

Lenin's point here is to show that Marx and Engels were always stressing a particular vision of what was to happen to the state with relation to the revolution. This, we have seen, is that the state will be smashed, its function taken over by the people for their purposes and society re-organized along communal lines, until such a time that all its functions can be taken over and performed by ordinary workers (i.e. until the state withers away).

Crucially, he's more at odds to show that this is not an anarchist proposal than the specifics being proposed by Engels at this point are practical or feasible.

To that end, his argument here is, at the very least, one that I'm able to make sense of given the previous three chapters. Whether he has the correct reading of Marx and Engels, is, perpetually, a question on which I just have to punt.

Still, I do find it strange that Lenin (and to the extent that he's right, Marx and Engels, too) thinks the reproduction of the renter/landlord relation at the state level--however temporarily!--as a virtue. One would have thought that if a person were homeless it's partially by virtue of the fact that they can't afford to pay for rent. To whom they pay that rent is, I imagine, irrelevant. So, I find it difficult to see why the fact that an apartment is now owned by the worker state rather than the landlord will solve the housing problem as long as both the state and the landlord demand rent that the homeless cannot afford. Rather than solving the problem, it merely relocates it somewhere else.

I suppose the obvious answer is that under worker control the rent will not be driven by supply and demand of housing, but will be fixed by the state such that those who need housing will always be able to afford it (until, of course, all housing becomes free after the state withers away). In that respect, perhaps what's being proposed is something like a temporary sliding scale of rent: everyone gets housing, but those who can't afford to pay rent (or those who can only afford to pay a little) don't have to, while others who can will continue paying rent until the state withers away. This seems like a plausible interpretation and seems go along fairly well with the whole "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" motto.

I suspect the full answer to this question is to be found in Engels' own writing rather than its summary by Lenin, but, as I stated in the first entry to this series, I'm only staying within the particular text.

2. Controversy with the Anarchists

Summary

Here, Lenin brings up a series of articles published by Marx and Engels against the Proudhonists. The controversy in question is precisely about the the Marxist position regarding the abolition of the state as set against the anarchist position.

Simply put, both Marx and Engels stress that they, like all socialists of the time (which included the anarchists), believed that the state would eventually disappear once classes disappeared. What they disagreed with the anarchists on, claims Lenin, is about the use of the state by the proletariat until that time, and, hence, the use of violence by the proletariat. "[Marx] opposed the proposition that the workers should renounce the use of arms, of organized violence, that is, the state, which is to serve to 'crush the resistance of the bourgeoisie.'" (Lenin, pg. 71).

This, then, is a question of means to a shared end. The anarchists and the Marxists both agree on the end, but whereas the former, claims Lenin, want to overthrow the state and then lay down their arms, the latter want to maintain the violent means of the state to repress their opponents until the state can, eventually wither away.

The same point is expounded on by Engels. He does this in the first place by ridiculing the notion that a society can do away with authority or structure all together in all domains of life.

Take a factory, a railway, a ship on the high seas, said Engels--is it not clear that not one of these complex technical establishments, based on the employment of machinery and the planned cooperation of many people, could function without a certain amount of subordination and, consequently, without a certain amount of authority or power?

Lenin, The State and Revolution, 72-73

In short, the doing away of all authority and all subordination is a pipe dream according to Engels and Lenin. The real question, then, is how the use of authority is going to be used with regards to the state. Here we get a fairly interesting quote from Engels:

The anti-authoritarians demand that the political state be abolished at one stroke, even before the social conditions that gave birth to it have been destroyed. They demand that the first act of the social revolution shall be the abolition of authority.

Have these gentlemen ever seen a revolution? A revolution is certainly the most authoritarian thing there is; it is the act whereby one part of the population imposes its will upon the other part by means of rifles, bayonets and cannon -- authoritarian means, if such there be at all; and if the victorious party does not want to have fought in vain, it must maintain this rule by means of the terror which its arms inspire in the reactionaries. Would the Paris Commune have lasted a single day if it had not made use of this authority of the armed people against the bourgeois? Should we not, on the contrary, reproach it for not having used it freely enough? Therefore, either one of two things: either the anti-authoritarians don't know what they are talking about, in which case they are creating nothing but confusion; or they do know, and in that case they are betraying the movement of the proletariat. In either case they serve the reaction.

Lenin quoting Engels, The State and Revolution, pg 73-74

In short, Engels claims that there can be no revolution without the use of force and authority by those who have won the revolution, and that to argue that such authority and force should be given up immediately after the successful revolt is tantamount to leaving the revolution open to its enemies.

As Lenin puts it in light of this, the anarchists' argument is decisively non-revolutionary. It's not that, as the Social Democrats say, this is a matter of one side recognizing the state and the other not. Rather, it's a matter of real, practical questions of how the revolution is to be done and what the revolutionaries should do with the state. Furthermore, in answering that question, Engels looks back to the last proletarian revolution--that of the Paris Commune--and not to some utopian ideal of how revolutions are played out in order to make his argument that state authority is the order of the day. In other words, what's learned form the Commune is the mistake of not using enough violence, and that a repudiation of authority at that stage of social development (though not permanently!) can only lead to ruin.

Analysis

On the whole, I find this section quite interesting, though not much new information is to be gleaned from it that we haven't gleaned form previous sections. Nevertheless, the quote from Engels is pretty interesting when it comes to offering a very succinct explanation about the different positions taken by anarchists and Marxists: they have a shared end, but differ significantly on the means by which they achieve it. They also differ greatly on the source of the problem with respect to which they adopt the same end--roughly, the Marxists see class society as the problem and the anarchists see authority as the problem (and before one is tempted to think that the shared similarities are enough to make the two positions ultimately the same, take a look at this previous post).

That quote from Engels also puts some pressure on some of Lenin's earlier commitments, or, at the very least, on what I ascribed to him as a commitment. Namely, it might seem that Engels believes that the complex nature of certain modern work necessarily requires a subordination to authority in order to be done. If a ship or a factory is to run at all, then some people must be subordinated to others. This, in turn, might seem to suggest that there are some jobs that are just too complex to be done by just anyone and that they must be done by certain people to whom others are subordinated. If so, then we might suspect that some of the bureaucratic tasks of the state are complex in just that way, requiring the subordination of certain masses to that of a ruling minority. Certainly, the running of the state is at least as complex as the running of a factory and the worry is that the prestige that accumulates as a result of belonging to a ruling group will be enough to create a split in the population and reproduce something like a class structure.

Here, it's important to note that there's a through line through this tension (whether that's successful is a different question). Specifically, it's important to note that what Engels seems to be concerned with is not a division of labor based on a difference in knowledge or skill needed of a job. It is perfectly possible that anyone can do any job on a ship or in a factory, but that nothing can get done unless there's some kind of subordination by some people to others. Thus, Engels seems to be primarily concerned with the need for authority to resolve certain collective action problems which will arise regardless of how competent the people involved in the enterprise are. What Engels is objecting to in speaking against the anarchists, then, is that they think they seem to be committed to a world in which there are no collective action problems. To the extent that they are committed to such a world (unlikely), the criticism is a valid one.

Still, one might still press the line I was pressing and ask why the necessity of authority as a way of resolving these problems within the state won't simply reproduce the same problematic conditions. Recall, further, that for Lenin, the dissolution of the state is primarily the result of the fact that the functions of the state will be able to be done by anyone. Does he in fact also think that there will be no collective action problems as a result?

Honestly, it's not clear. However, there's a different line of reasoning that might work. Namely, it's important to remember that what matters for Lenin is less the existence of certain authoritative structure and more of whose interests the authoritative structures serve. One of the problems with the existing state structure is that the interests it serves are the capitalist minority. They come to do this because those who own the means of production buy them and influence them to serve their interests. This is not a problem, presumably, if the authoritarian structure comes to serve the interests of the people. As long as that's the case, its authoritative status is not a problem. Indeed, this is part and parcel with what he believes the state must come to be during and following the revolution.

So, the real question is not about whether or not there will be the use of authority of the proletarian state--we already know that there will be. Rather, it's a question of how it can be maintained that the authority of the state will always be used in the interest of the people. And that, we've been told, is done precisely by the creation of a cheap government in which everyone is paid the same and everyone can do everyone else's work. In other words, the idea seems to be that anyone who comes to wield more power than they should will never be able to turn on the people because he or she will be always replaceable. Crucially, this goes even for the people who must wield authority for the purposes of resolving collective action problems. If Josef D. is getting too big for his bureaucratic britches, then it's just a matter of replacing him with Leon T. who can do the job just as well (and so on and so on).

I don't know if that's what Lenin was going for, and a number of other practical questions arise as a result (who has the power to replace?) but I can at least make sense of what's being said here.

3. Letter to Bebel

Summary

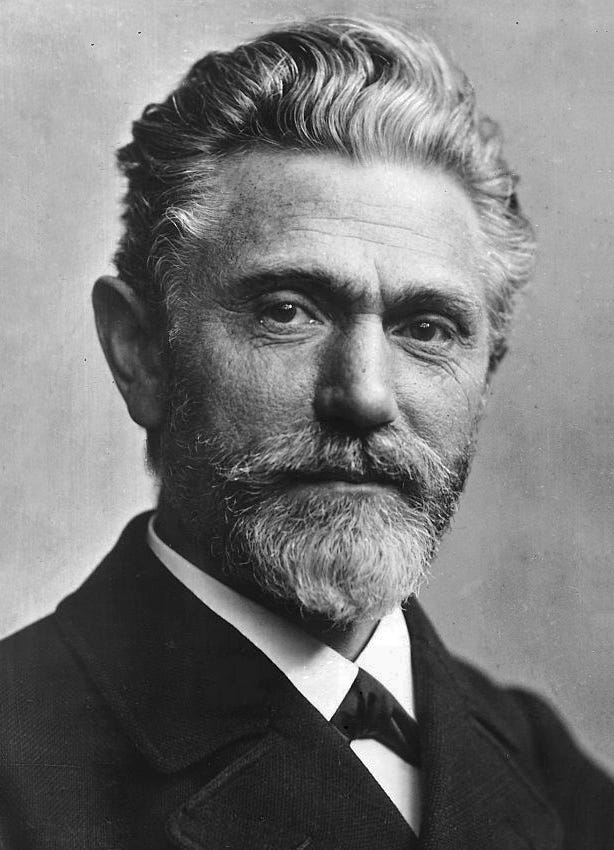

In March of 1875 Engels writes a letter to Ferdinand August Bebel (one of the founders of the German Social Democratic Workers’ Party) in which he criticizes the Gotha Program and, in particular, the role of the state taken up in that program. Lenin draws specific attention to the fact that Engels insists that the term “state” should be replaced with the term “community” in the program.

Engels’ argument is as follows: Once the state stops oppressing the majority in favor of the minority, it ceases to be a state. Talk of a ‘free people’s state’ or a ‘people’s state’ just doesn’t make sense since when it is in the hands of the proletariat it is no longer a state but simply a tool to be used to “hold down its adversaries.” Once this has been done—once the people are free—then there just is no state. What’s left behind is something else; viz. a community. Lenin restates this argument, then, in typical fashion uses it to rail against Kautsky, and to assure the reader that the Bolsheviks are completely on board with the proper orthodox Marxist line.

Analysis

I have very little to say about this section since nothing terribly new is being brought in. This does seem to be more grist for Lenin’s mill in claiming the mantle of the most-Marxist Marxist around, but that’s about it.

4. Criticism of the Draft of the Erfurt Program

Summary

In this section Lenin brings in Engels' criticisms of the Erfurt Program proposed by the Social Democrats as further support for his understanding of the role of the state.

Lenin focuses on three points that Engels brings up with respect to the state's role in the program. The first and biggest one has to do with the fact that there's no call for a republic within the draft. Engels thinks that the current German constitution is simply a "fig leaf" over the reactionary absolutism of 1850 which only legalizes and formalizes an unjust order. Furthermore, he criticizes the SD in claiming that the only reason they're not calling for a republic is because of fear of a reactionary backlash and the re-institution of anti-socialist laws. This, claims Engels, is an opportunist move and only serves to support the absolutists and reactionaries--they forego the pursuit of a principled end for the achievement of short term Pyrrhic victories. In Engels' eyes, the democratic republic is the nearest approach to the dictatorship of the proletariat and there is no future for the proletariat that doesn't go through a republic but only seeks to make peace with the status quo.

As Lenin puts it:

For such a republic--without in the least abolishing the rule of capital, and, therefore, the oppression of the masses and the class struggle--inevitably leads to such an extension, development, unfolding and intensification of this struggle that as soon as there arises the possibility of satisfying the fundamental interests of the oppressed masses, this possibility is realized inevitably and solely through the dictatorship of the proletariat, through the leadership of the masses by the proletariat.

Lenin, The State and Revolution pg. 84

In short, the move towards a republic makes it possible for the proletarian revolution to kick off once the contradictions of capitalism have come to a head.

This is the first practical suggestion Engels makes in criticizing the program: include a call for a republic. The second suggestion--in the same vein--is concerned with the model of the republic that is called for. Specifically, Engels holds that the SDs should be primarily fighting for a unitary republic and not a federal republic (although he grants that the latter may still be a step forward in some cases; viz. those in which multiple nations span the same geographic locale). In a unitary republic the provinces or individual states within the republic are all held by a common central aim or commitment to the republic. By contrast, a federal republic is one that is divided by the state in separate units. The difference, then, can be thought of as the difference between a top-down approach in which unity is forced by and the state and then partitioned by it, and a bottom-up approach in which unity is achieved through the cooperation of different autonomous parts who unite in a single state.

This is made all the more apparent when Engels speaks about the local governance of these individual units and claims that there should be "complete self-government for the provinces, districts and communities through officials elected by universal suffrage. The abolition of all local and provincial authorities appointed by the state." (pg. 87) This, once again, reinforces the building of a bottom-up unity (we elect our officials locally and then participate nationally) rather than a top-down imposed federalism (we elect someone to the state who then appoints local officials).

All of these remarks are, of course, intended to show that Lenin has the right reading of Marx and Engels and that a proper orthodox Marxist is in favor of a democratic centralism and not whatever it is that the anarchists are calling form.

Analysis

I might be misreading either Engels' remarks of Lenin's analysis of them, but this section seemed to me to be less in support of Lenin than he takes them to be. Perhaps part of this is the fact that I don't quite understand the different models of federalism that Lenin and Engels seem to have in mind in drawing their distinctions. I don't, for example, know what the Swiss federal model is and why that kind of model is much worse than a different kind of federalism.

It also strikes me as odd, perhaps because of some unfair historical foresight on my part, that the models for self-governance advocated by Engels and Lenin is the republicanism of America and the former British colonies. Part of the reason why I think it's odd is that the model that we know ends up being used in the USSR is precisely not the one that Lenin and Engels are pushing here. Rather, it seems to be precisely the 'bad' kind of federalist republicanism which operates from the center to the periphery. Within the Soviet Union, Russia was always the central player who dictated to the other members, and within the individual states within Russia (to the best of my knowledge) rule always flowed from the central party to the provinces, and not the other way around (but I could be mistaken).

In any case, I suppose it warrants saying, once again, that Lenin is writing this having had zero experience in state power (the perennial irony of all this is, of course, the fact that Marxism is supposed to be uniquely positioned to prevent precisely this kind of armchair speculation by drawing attention to the particular material conditions on the ground...though, of course, Lenin was also convinced that he knew those conditions). The second thing to keep in mind is that although Lenin is still bringing in some of this stuff to buttress his position against the anarchists ("see, Engels was about democratic centralism too!"), the group that he seems to be primarily addressing here is that group that is one that's on his right--namely, those democratic socialists who might want incremental change within a system.

Still, it seems to me that these very same passages from Engels could be seen as going against Lenin's theory of revolution. Recall, Lenin doesn't want a bourgeois revolution before the socialist revolution. Rather, he wants to go directly to the latter without the former--it's to that end that the violent smashing of the state and the dictatorship of the proletariat is to be used. Yet, here, we have seemingly clear arguments from Engels about why a republic needs to be established first so that when certain conditions come to hold, then we can have the proletarian revolution. Why this isn't a place where Lenin is being heterodox is unclear to me.

5. The 1891 Preface to Marx's The Civil War in France

Summary

In this preface Engels is summarizing the lessons learned from the Commune with the benefit of a 20 year hindsight. The first lesson, Lenin notes, is that the central question regarding the success of a worker's revolution is that of who is armed. Hence, Engels' claim that "the disarming of the workers was the first commandment for the bourgeois who were at the helm of the state. Hence, after every revolution won by the workers, a new struggle, ending with the defeat of the workers." (89) For Lenin this is, of course, yet another reason to support a violent and armed revolution, but it is also an opportunity to throw some jabs at some of his old opponents, and in particular Tsereteli (see note below explaining what he's getting at).

Following this is a minor note about the role of religion that seems to pertain only to the stance taken by the German SDs. Citing Engels's statement that "in relation to the state religion is a purely private matter," the SDs had taken the position that religion was a private matter tout court. Lenin corrects this by saying that this is a misinterpretation of Engels and that Engels' remarks by no means meant that religion was a private matter in relation to the party. This remark seems to go nowhere other than to air out Lenin's grievances against people whom he thinks don't understand Marxism as well as he does.

Returning to the main point, Lenin tells us what the two main lessons learned from the Commune were with respect to the state. They're familiar ones:

First, it's that the state remains the state even in a democratic republic. It remains a tool of class oppression even if democracy is on the scene. The Commune had realized this and knew that as long as the state officials remained in their old capacities and still served as "masters of society" the working class couldn't survive. To do so, it would need to do away with all previous state machinery and smash it.

Second, in order to smash the state machinery, the Commune had to transform the state officials and their roles from masters of society to servants of society. The Commune did this precisely by electing officials anew, making all of them recallable, giving them all working wages so as to stop opportunism and career hunting, and by imposing strict term limits.

Lenin then repeats that curious claim that the abolition of the state requires that the functions of the state be "converted into the simple operations of control and accounting that are within the capacity and ability of the vast majority of the population, and, subsequently, of every single individual." (92). This, again, to stress, is what is needed in order for the state to be smashed--its machinery must be converted into this so that careerism and prestige become impossible. Once that is the done, the state loses its function as a tool of class oppression, the jobs it provides gain the status as ordinary jobs, and it slowly begins to wither away.

So much should already be familiar. Following this recap, we get a curious little passage about a mistake Engels doesn't make. Namely, "Engels did not make the mistake some Marxists make in dealing, for example, with the question of the right of nations to self-determination, when they argue that this impossible under capitalism and will be superfluous under Socialism." (93). What's normally conflated is unclear (I'll take a whack at it below), but it is followed by a less familiar claim by Lenin which I quote it here in full:

To develop democracy to the utmost, to seek out the forms for this development, to test them by practice, and so forth--all this is one of the constituent tasks of the struggle for the social revolution. Taken separately, no kind of democracy will bring Socialism. But in actual life democracy will never be "taken separately"; it will be "taken together" with other things, it will exert its influence on economic life, will stimulate its transformation; and in its turn it will be influenced by economic development, and so on. Such are the dialectics of living history.

Lenin, The State and Revolution, 93

This remark isn't elaborated on at all. Rather, Lenin moves on to really stress that Engels' warnings were perennially about knowing the true nature of the state:

In reality, however, the state is nothing but a machine for the oppression of one class by another, and indeed in the democratic republic no less than in the monarchy; and at best an evil inherited by the proletariat after its victorious struggle for class supremacy, whose worst sides the victorious proletariat, just like the Commune, cannot avoid having to lop off at once as much as possible until such a time as a generation reared in new, free social conditions is able to throw the entire lumber of the state on the scrap heap.

Lenin quoting Engels, The State and Revolution, 94

Engels gives this reminder especially to comrades in Germany, but the message is clear: don't romanticize the state simply because it has taken a different form--it's still the old enemy in new clothes. Lenin's advice to his contemporaries is equally clear: this is why we shouldn't work through the state without first smashing it; if anyone works with the state they should only do so reluctantly and never eagerly.

Finally, Lenin ends by remarking that although he agrees with Engels that the state remains a state even when democracy has entered the scene, this doesn't mean that either of them think that the state has the same form in both monarchy and democracy. Far from it, a more open and freer class struggle is possible in the latter and not the former, and hence, we should be in favor of the latter (but for that reason and not because some kind of magic happens once democratic processes are in place!).

Analysis

I promised a bit of historical information regarding the Tsereteli remark so let me begin by addressing that. Lenin here is referring to a speech Tsereteli gave on the occasion of banning a planned Bolshevik demonstration on June 10th. The demonstration was, according to the Bolsheviks, supposed to be a peaceful one, but the grounds on which it was banned by a block of Mensheviks and SRs (Tsereteli himself was a Menshevik) was essentially that the radical nature of the Bolsheviks would be used as a justification by the Provisional Government to disarm the workers. I couldn't find the original Tsereteli speech, but his argument appears to be "your radical revolutionary tactics are likely to sink the whole revolution; once the workers are disarmed, the whole thing's over. So, we're banning you from doing what you were planning for the sake of the revolution." Lenin's response in return seems to be that this very muzzling of revolutionary tactics is itself counter-revolutionary (a kind of "oh, so what are you doing in de-facto disarming us and not allowing us to demonstrate? Are you not playing the game on bourgeois terms?"). Hence, his claim that this was really the breaking point when the SRs and Mensheviks broke apart from the true revolutionary purpose.

Apart from this explicit reason, the SRs and the Mensheviks were, in all likelihood also trying to swing their weight around a bit and send a message to the Bolsheviks that despite their name, they still represented the minority in their coalition and that they should step in line. They score a small victory on that front in the so-called 'July Days' when mass street violence is blamed on the Bolsheviks, the party leaders are arrested or scattered, and Lenin is forced to go into exile. Ultimately, however, we know that the Bolsheviks have the last laugh.

Setting that aside, what should we make of the rest of the section. I don't have much more to say about the elements that are repeated here regarding the smashing of the state, other that to say that I'm more and more convinced that I was correct earlier in my interpretation of a 'smash' being used as a technical term and in my claim that a lot hangs on this empirical assumption Lenin makes about what smashing requires (i.e. the transformation of all state functions into simple processes that can be done by anyone). That's not to pat myself on the back since it only means that I can still read, but sometimes you gotta take pleasure in the small things.

Rather, I want to focus on the latter half of the section and in particular on that strange passage that I quoted in full above. I have a very hard time understanding what Lenin is trying to say there. It's clear that he's drawing a distinction between democracy as it can be understood when 'taken separately' democracy as understood when 'taken together', but this distinction is still opaque. My best guess is that this is a distinction between looking at any particular form of democracy and looking at what a full democracy requires. To think of democracy in the former sense is just to be concerned with what institutional features one's political system has (i.e. is it representative, is it direct, etc.); to look at it in the latter sense is to be concerned with what genuine self-rule by the people actually needs (i.e. ???).

From that perspective Lenin's point seems to be that there is no single kind of democracy such that when it is established, Socialism simply follows. It's not as though instituting universal suffrage will suddenly transform the existing system into a utopia. Quite to the contrary, achievement of absolute democracy is a wholistic and dynamic thing that requires constant adjustments, experimentation, and sensitivity to the totality of how people live. In that sense, the work towards achieving a more perfect democracy is always in progress--even if you achieve it for a certain time period, conditions on the ground might change and require new ways of adapting.

If correct, then Lenin's direct point to his contemporaries was that they shouldn't be merely striving to achieve a democratic system. That by itself isn't going to do anything and it certainly won't automatically bring about the socialist revolution. As both Lenin and Engels stress, the introduction of a certain political structure is useful for the waging of a more unconstrained class struggle. This is a proximate goal towards an ultimate one and Lenin is really reminding us not to forget that.

[This reading also makes sense given the surrounding quotes by Engels, and especially the one used to chastise the Germans about their state fetishism. That makes me feel pretty confident about my interpretation, but I could be mistaken.]

One thing that I especially like about this passage (if my reading is correct) is that it highlights a certain flexibility of tactics of Lenin's and provides us with a little window of what he envisioned the socialist future to look like. One of the unfortunate results of Stalinism (though by far not the worst) is that it turned socialism and socialist thought into something rigid and ossified (though, to be fair, shades of this are present in Lenin, too, with his obsession with the correct reading of Marxism). But it's clear here that this was never what it was supposed to be and that it was envisioned to be something incredibly flexible and agile in response to the workers' needs.

This view is also in stark contrast to the general ways in which so many people think about the current political and economic system. Here I have in mind the popular moderate view that capitalism has solved all fundamental economic problems, that Locke solved all fundamental political problems, and that all other problems are just a matter of implementing different wonkish tweaks to those two systems. This, too, is a rigid and ossified "end-of-history" way of thinking about things that I find particularly frustrating and it's interesting to see the outlines of an alternative way of at least thinking about these questions (even if the lessons of history suggest that at least part of this approach is mistaken).

6. Engels on the Overcoming of Democracy

Summary

The general question this section aims to address is why Engels believes that the removal of the state will be complete with the arrival of a new generation. The answer comes after a rather weird digression into the proper party name. Here, Lenin quotes Engels on why he and Marx preferred the label 'communist' to the label 'social-democrat'--in short, they felt that 'Communism' described precisely the aims towards which the proletariat should be striving, while 'social-democracy' gave the impression that one of the aims that the party should be striving for is the preservation of democracy. The term 'social-democrat' can 'pass muster' for Engels so long as this mistake isn't made and the party doesn't take the label literally but instead remains true to the more basic principles.

After proposing that the Bolsheviks take this cue to change their name to the Communists (with 'Bolsheviks' in brackets) to better reflect their principles, Lenin gets to the heart of the matter. Engels' point is that overcoming the state means overcoming democracy--when the state withers away, so does democracy. Lenin admits that this might sound bizarre and incomprehensible and grants that "indeed, someone may even begin to fear that we are expecting the advent of an order of society in which the principle of the subordination of the minority to the majority will not be observed--for democracy means the recognition of just this principle." (97)

However this is not the case because, as the alert reader may have already intuited, 'democracy' in this sense has a technical meaning. Lenin explains:

Democracy is not identical with the subordination of the minority to the majority. Democracy is a state which recognizes the subordination of the minority to the majority, i.e., an organization for the systematic use of violence by one class against the other, by one section of the population against another.

Lenin, The State and Revolution, 97

To overcome democracy is to overcome the state is to overcome the very use of violence for the purposes of subordination. This is the Communist aim which Lenin reiterates:

In striving for Socialism we are convinced that it will develop into Communism and, hence, that the need for violence against people in general, for the subordination of one man to another, and of one section to another, will vanish altogether since people will become accustomed to observing the elementary conditions of social life without violence and without subordination.(97-98)

Lenin, The State and Revolution, 97-98

And this overcoming itself requires the arrival of a new generation that can be subject to this kind of habituation. By growing up in such an environment and internalizing it fully from birth, this new generation is finally able to dispense with the state once and for all.

Analysis

Despite the fact that this is one of the shortest sections in this chapter, I find it to be one of the most interesting and illuminating ones. I myself raised the question several chapters ago about why the destruction of the state would mean an end to the process of deliberation by democratic means. The answer that we get here is that that process isn't eliminated. What's eliminated is the concept of the democratic state which is the means enforcing the will of the majority by violence on the minority. This is part of what Lenin means when he says that democracy in his sense is not identical with the principle that operates in the process of democratic decision. It's not identical because the former includes more that the latter insofar as it incorporates the element of coercion and violence against the minority to enforce the will of the majority. That kind of democracy is the kind that Engels and Lenin think is overcome when the state has withered away.

What remains in its place? Well, presumably, the principle itself minus the violence. But what does that mean? It means that the majority dictates and the minority submits willingly. Furthermore, we see that this is supposed to happen because, by growing up a certain way, people have become accustomed to a world in which this is the case.

A couple of really interesting things are worth pointing out here. The first is Lenin's picture of psychology. Specifically, it seems to be entirely modeled on a kind of conditioning or habit based picture. In short, it seems to assume that changing the environment in which one becomes habituated makes a massive difference to behavior. In the useless debate about nature versus nurture, Lenin is strictly in the nurture camp. This, as some of Lenin's other assumptions about the nature of bureaucracy and epistemology, is, to a certain extent an empirical matter but one that is taken for granted for Lenin.

In saying this I don't mean to suggest that I think the opposite is true--i.e. that really, human nature is in some respects immutable and that Lenin just didn't see that. People rarely notice how bad of a track record that argument has had when particular examples have been brought up historically; there are so many things that supposedly were part of human nature that we could never curb but which we've learned to do fairly well without (pick your favorite piece of racist or sexist philosophy from history if you want examples). As far as I'm concerned, human nature is much more malleable than people give it credit for.

What I do want to say, however, is that Lenin's picture of human psychology is much too simplistic. And here, the reactionary might have a point. Perhaps human nature is very malleable but is not malleable with respect to one or two very specific things. Perhaps, pace Nietzsche or Hobbes, it is not malleable with respect to its desire for asserting its will or its selfish drive. And if what is necessary to willingly submit to the will of the majority is that one fundamentally change that aspect of humanity, then we might be in trouble.

[For what it's worth, I think such arguments are also overstated. More conservative folks will tend to treat the Nietzschian or Hobbesian claims as a kind of established empirical dogma. It's not--it just seems more plausible to them that people are naturally selfish or that they want to assert their will and the support needed for that claim is black-boxed.]

Alternatively, it may also be the case that the environmental conditions that would produce the desired results require more than the elimination of class. This is the second interesting point. One of the fundamental assumptions that has been brought up before and that appears again here seems to be that the source of all macro-scale social antagonisms is due to class and that the removal of class leads to the removal of all such antagonisms as well. Everything in Lenin's political theory ultimately points to and aims at class struggle and overcoming class struggle. This, in turn puts a lot of weight on both the concept of class and that of class struggle, and one might have serious reservations that they can handle all that weight. After all, one might think that questions of race, sex, religion, gender, etc. also make a difference to macro-scale social conflicts and those questions will continue to exist even if class disappears.

This isn't a new concern, of course, and the standard solution has been to adopt some kind of class reductionism to explain why each of these other issues really amount to issues of class as well. I'm not unsympathetic to this kind of reductionism (in fact, I think it's more reasonable than people suppose it is), but it, too, needs to be defended separately and cannot be assumed automatically.

Finally, it's worth also thinking about the principle that Lenin identifies with the 'good' kind of democracy--namely, the principle of the subordination of the minority by the majority. In one respect, I think he's right; when democracy works well, this is precisely what happens. Furthermore, when looking at it through the lens that assigns capitalists as the minority and the rest of the world as the majority, then, it's clear that capitalism presents a perversion of democracy of the highest order. However, it seems obvious that a full adherence to that principle also allows for a tyranny of the majority in certain other contexts. This is all the more obvious if we consider that issues of race, gender, etc. can still persists even in a system in which there are no classes. In those cases this principle becomes fully tyrannical and oppressive.

This, of course, brings us back to the first two points. If all macro-scale conflicts really are the result of class, and if class is removed, then whatever is left over won't be one of the cases in which submission to the majority constitutes tyranny. After all, the city council isn't tyrannical when it builds a school in that place where five people wanted to put a bar. If all cases of submission to the majority after the end of class struggle are such, then there's not much to worry about. Likewise, but in a much more cynical frame of mind, if there are still some such cases that aren't eliminated by the end of class struggle, but if such conflict can be avoided by conditioning people to think differently about their submission, then the worry, if not fully abated, is at least shifted.

I take it this latter option is actually highly unattractive to most people (myself included) since it seems tantamount to the development of a kind of mass adaptive preference towards the good of the majority and away from the individual's good. This is especially worrisome if it is supposed to be applied to questions that aren't merely incidental, but are constitutive of what is really required for people to thrive. If, for example, the majority required the suppression of a minority's sexuality and if sexual expression is constitutive of the good life, then the option just suggested is pretty much that of brainwashing and depriving individuals of something really valuable.

This, I should stress, is not a Marxist view. The core of Marxism as I see it is very much concerned with the flourishing of human beings and with providing the means by which that can be done. Clearly, this picture of flourishing doesn't include "privately owning the means of production for the advancement of capital" as a way to flourish so it will exclude some means (and anyone who thinks this is a way of human flourishing is so deep in ideology that I'm genuinely surprised they've made it through FOUR of these impossibly long blog posts about LENIN). But it does (or should) include a plurality of others. Human flourishing is not a democratically determined thing, though it is, at the same time, not something that is independent of what people think it is either! The point here is that I'm skeptical of any treatment of Marx that allows for or counts on such unprincipled tyrannical excesses and I see neither Marxism (nor Leninism for that matter just yet) as necessitating such moves.

All this is to say that perhaps the full weight of the problem falls back on the question of whether all serious macro-scale social problems can be reduced to class problems such that those problems that remain in wake of the revolution aren't worth taking seriously. If that can be shown, then most of my concerns would be abated.