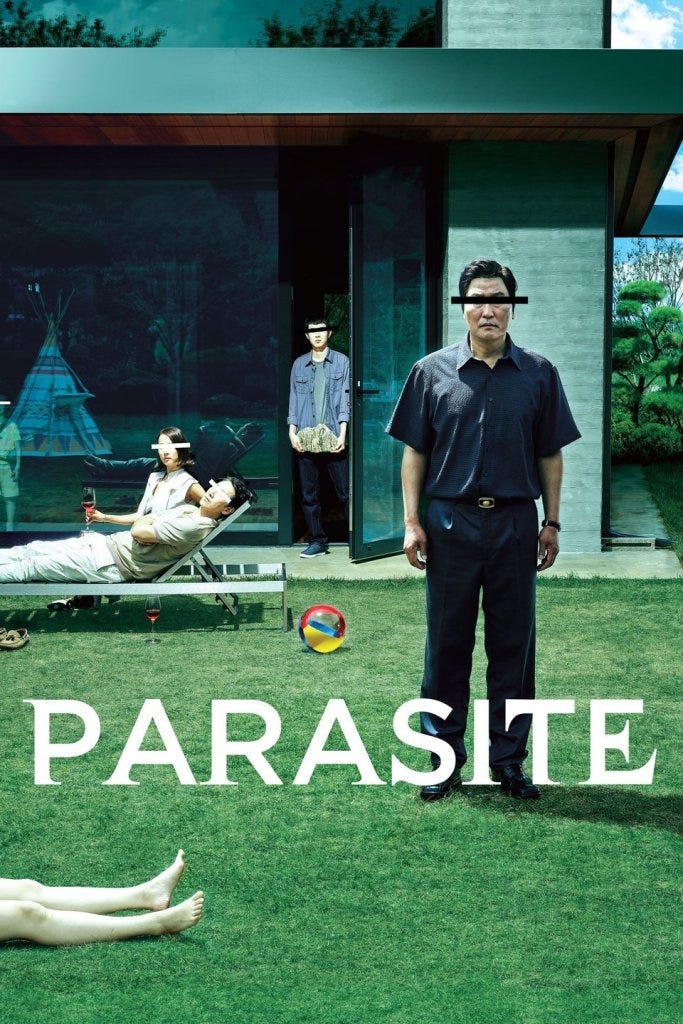

Some Thoughts on "Parasite"

I went to see Bong Joon-Ho's Parasite last month and came out of the theater absolutely pumped. I've seen more than a few great movies this year, and this one definitely ranks among the top. I meant to put down my thoughts about the movie on paper much sooner, but the end of the semester grading (and my previous commitment to finishing The State and Revolution) kept me from doing it sooner. In any case, what follows below are a couple of things that I really liked about the film (and one thing that I didn't care for too much). Plenty of spoilers follow.

What I Loved:

Perhaps the thing I liked most about the film is its focus on the impact and importance of the material conditions on the two families. This is, of course, most clearly demonstrated in the difference between the homes of the Kim and Park families. The Kim family lives in a small, cramped, smelly, sub-basement apartment in a poor part of town. The audience gets the impression that this is less of an apartment for people as much as it is a kind of negative space that's occupied by people (much in the same way that the space underneath the fridge is the space that happens to be occupied by cockroaches). It is distinctively and oppressively urban.

By contrast, the Park family lives in a spacious, elegant, beautifully designed house elevated above the city. Its landscape is so carefully manicured and maintained that when one looks out of the massive Park house windows one can imagine that they're not anywhere near an urban center. The house not only suggests a life of elegant opulence, but also one of privacy--every family member has their own separate space and there are no drunks peeing in sight of the dinner table.

In fact, there's a glut of privacy in the Park house. Only in a house like that could a man live underground without ever being noticed; only in a house like that could so many secrets be kept. The Kim family is able to trick the Parks because each of them can occupy a role that fills a space within their house. In turn, by playing that role well enough and occupying that space, they can slip by unnoticed. Clearly, the same thing could never happen in the Kim house.

These most-obvious material differences are important, but they merely scratch the surface. After all, it's not uncommon for movies to bring the viewers' attention to great disparities in wealth and if the most notable thing about the movie were to make us notice that some people live comfortably and affluently while others don't, then it wouldn't be worth writing about.

What Parasite does especially well is explain how these differences in material conditions have massive effects on the psychologies of the characters. And it does so without resorting to a kind of moral caricaturizing. Let me explain by starting with this latter point and working backwards.

a. No Moral Caricatures

First, it’s clear that the Parks aren’t pure incarnations of evil. It’s true, they do live an affluent lifestyle, but they’re never shown to do anything particularly heinous. Mr. Park doesn’t work as, like, an arms dealer, and although Mrs. Park is shown to be a bit naïve and childish, it’s clear that she clearly loves her children and wants the best for them. Their relationship with the Kim family isn’t particularly warm (they are, after all, ‘the help’ and the Parks frequently talk among themselves about Ki-taek’s smell), but they’re neither cold nor particularly imperious. In short, they perfectly embody a kind of familiar elite aloofness which, in general, is not enough to make the audience hate them.

By contrast, it is equally clear that the Kims are not paragons of virtue. In the first place, they are willing to lie to and manipulate the Parks in order to get what they want: Kevin is not a tutor, Jessica is not an art therapist, Ki-taek is not a professional driver, and Chung-sook is not employed by an elite house-keeping service. These deceptions are not terribly serious since the members of the Kim family are more than capable of doing what the Kims need them to do--they may have lied about their qualifications, but they do their jobs well.

[That being said, the Kim children also do some pretty objectionable things: Kevin almost immediately initiates a romantic relationship with the much younger girl he’s meant to be tutoring, and it's not obvious whether Jessica’s ‘art therapy’ is really helping the young Da-song.]

Much more objectionable are the lengths to which the Kims go to secure their position with respect to the other working-class people. First, in order to get her father hired as Mr. Park's driver, Jessica gets his previous driver fired by implying that he's having sex in Mr. Park's car. And, of course, in order to get Chung-sook hired as the housekeeper, the family causes her to have a sever allergic reaction which could have killed her (indeed, later, they do just that).

The Kims’ motivation throughout the movie is exclusively self-centered. What matters to them is that they’re able to get what they think they’re able to get. That doesn’t mean that they’re willing to do anything—they never intend to kill the Parks’ former housekeeper—but the audience gets the sense that the welfare of people outside the family matters very little to them. In short, they’re selfish, opportunistic, and largely amoral. Of course, that doesn’t make them monsters, but it does make the audience’s perception of them much more complex, and, in my experience at least, much more realistic.

b. Material Conditions Shape Psychology

By refusing to make the Parks and the Kims into opposing moral caricatures the director is able to move beyond a naïve picture that explains the characters’ actions and psychology through a purely moral lens. Neither the Parks nor the Kims do what they do because they’re simply good/evil people who are naturally moved to be selfish, or cruel, or indifferent to the suffering of others. This, in turn, draws the audience’s attention to the alternative explanation: namely, that the families’ respective psychologies and motivations are shaped precisely by the material conditions in which they live.

This is perhaps the most important theme in the movie and one that I think was done fantastically well. One scene to note here is the scene in which the former house-keeper and her husband are discovered by the Kim family as they squat in the Park family house. The two families mirror each other here: both are destitute, both are desperate, both are trying to alleviate their suffering by living off the scraps of the Parks, and neither is willing to give up their temporary gains for the benefit of the other. They are, in short, both parasites (THAT’S THE NAME OF THE MOVIE! GET IT?!?!). Crucially, their recognition of equality in this situation makes the two of them competitors for those scraps. Both families realize that their relative well-being is contingent on the zero-sum gains they’ve been able to attain behind the Parks’ backs, and that the opposing family is in a position to ruin their setup by alerting the Parks. This realization culminates in the fight between the two families, and, ultimately, in the death of the former house-keeper and the imprisonment of her husband in the underground lair.

This scene (as well as the scenes in which the Kims succeed in getting their positions in the Park house) is a metaphor for the broader phenomenon in which the conditions of poor people force them to turn against one another in order to get the scraps left by the rich. It’s not the case that the Kims hate the former house-keeper and her husband—they don’t set out to kill her—and vice versa. But the situation they’ve been presented with is one in which they must either fight each other and preserve what they’ve gained, or give that up for someone else to grab while they return to their previous lot. Scarcity and poverty are what motivates the families' behavior and what explains their actions, not anything about their inherent moral character or worth.

The psychological warping of the individual in this setting is most clearly seen in the behavior of Geun-sae, the former house-keeper's underground dwelling husband. His subterranean life has led him to see Mr. Park as a kind of God-figure to whom reverence and submission is owed. Far from seeing his life as the manifestation of a gross injustice in which a select few get to enjoy the finest things in life while the many fight over scraps, Geun-sae sees himself as a beneficiary of a blessing bestowed to him by Mr. Park. In that sense, Mr. Park doesn't appear to him as another human being, but rather as a supernatural entity with the power to give and take away life.

This reification of the wealthy is a familiar phenomenon and is at the core of capitalist ideology. In that ideology, the capitalist appears almost as a force of nature who produces value from nowhere for the benefit of others, and who, of course, grabs a share of those benefits in the process. Thus, the capitalist is seen not as someone who grows fat off the exploitation of others, but as someone who is the source of all that is good in life.

Now, this is quite literally the case for Geun-sae for whom day-to-day survival depends on the well-being and success of Mr. Park. But the same phenomenon is found in a lesser degree in the way ordinary people and politicians treat the rich as 'job creators'; in the way the 'entrepreneurial spirit' is idolized; in the belief that influx of wealth 'fixes' neighborhoods; and so on. Indeed, there is a general dogma (at least in America) against doing anything that might disrupt or go against the interest of the rich since to displease them would cause them to withdraw their blessings from the people. Sacrifices must be made to the Gods of Capital--taxes must be forgotten, credit extended, markets opened, communities destroyed--so that something worse, we are told, doesn't happen; viz. so that Amazon doesn't move its headquarters to Northern Ireland, so that Carrier doesn't close its plants in Ohio, so that Blue Cross/Blue Shield doesn't lay off a thousand workers. This is just Geun-sae's supplicating attitude to Mr. Park writ large.

c. Luck, Rationality, and Contingency

Perhaps the most interesting aspect in how differences in material conditions affect individuals' psychology is in the realm of rationality. This can be seen in one of the film's pivotal scenes in which a deluge washes over the city, flooding the Kim family's basement apartment, destroying all their belongings and leaving them homeless.

In the first place, this scene is interesting for the contrast between the way the same contingent event--the rainstorm--affects the Kim and Park families. For the Kim family the storm is unquestionably devastating. In the span of a couple of hours, while fantasizing about the kind of lives they'll have if they continue to hold their positions in the Park household, all of their belongings are completely destroyed and they're forced to take shelter in a relief center for the foreseeable future. By contrast, for the Park family, the rainstorm is a blessing that clears away the pollution and freshens the air.

This by itself is interesting, but it points to an even more serious point. Namely, it shows how absolutely devastating the role of luck can be in how well one's life goes. Let me back up a little bit. Aside from fetishization of the wealthy, another lynch-pin in American capitalist ideology is the myth of the self-made man as the product of rational calculation and prudent risk. As it goes, the rich do not make their money through exploitation, but first by diligent saving and then careful study and investment in what the market needs. In short, successful rich folks are those who have an ability to suppress their immediate desires and delay gratification in a rational matter that maximizes their yield. In contrast, the poor are often seen as irrational, lazy, or chronically incapable of suppressing their immediate urges for the sake of greater future gains.

This is what's in the background when people claim that poor people are that way because they spend all their money on cars, clothes, and toys rather than saving it and investing it (this, and, most of the time a hefty dose of racism, too). Indeed, I've even heard it said that poverty is perpetuated because poor people buy coffee from Starbucks or eat fast food rather than making either at home! In short, poverty is seen as an inability to manage a budget, and managing a budget is seen as an exercise in rational planning for the future. (For more on this kind of argument and why it's wrong, see UNC's own Jennifer Morton's work on poverty and rationality)

The deluge scene in Parasite shows just how stupid this line of reasoning is in light of the actual material conditions on the ground. In one of the best scenes in the movie, Kevin asks his father in the shelter what the plan is. Ki-taek responds (paraphrasing) that the plan is the one that succeeds every time: namely, the one that isn't made. Ki-taek's point is, of course, not an endorsement of a kind of irrationality, but rather the very prescient one that the norms of rationality that the myth of the rational capitalist endorse only make sense under certain background conditions. Specifically, they only make sense if there's a certain kind of security against these absolutely devastating contingencies that can completely destroy your life in the span of a few hours. It simply doesn't make sense to live the kind of life that looks years, months, or even weeks in the future if tomorrow a rainstorm can take everything away.

Now, it's true that, in a certain respect, we are all subject to the whims of fate. Both I and Jeff Bezos can be crushed by a falling piano tomorrow; we may both be struck by lightning; and we may both develop some rare, terminal disease. No amount of rational planning will guarantee that these things won't happen and this is something that is shared by all of us regardless of wealth or economic status. At that level, we're both equally vulnerable to luck. Nevertheless, at every level below that, the difference become astronomical. An unexpected root canal won't force Jeff Bezos to take out high-interest loans; a family member falling ill won't make a difference as to whether he'll be able to work; etc. With respect to most (though not all!) contingencies, Bezos is protected while I'm not. What this means, of course, is that he can discount certain events when making certain decisions and that certain actions are rational for him that wouldn't be rational for me.

Much further down the line are the Kim family. The question that their situation raises is about how one should live when virtually anything can ruin any plan that you have in the future. Is it even rational to spend the energy to form plans when you live in that kind of world? Ki-taek's answer is, of course, no. Not only is there no sense in planning under such circumstances, but it's absolutely a waste of time. Instead, these conditions suggest that one should live with the short-term in mind--with getting fed today; with getting to work today--rather than with some unattainable and implausible future further on.

This is something many people who haven't actually been poor have a hard time understanding, and it's something that I think the movie presents very well.

d. The Central Question

All of this serves to highlight what I take to be the central message of the film. The title naturally invites the viewer to repeatedly ask the question of who are the 'parasites' in this film, and, in turn, to wonder whether they are justified in 'feeding' off others. But these questions are not the most important ones. With respect to the first, there's no question that the Kim family (and the former house-keeper and her husband) are the parasites--in that respect the metaphor is almost too on the nose. The second question is a bit more interesting, but the points I've brought up--specifically, the fact that none of the characters can be caricatured as people who 'deserve' their lot, and the effect that the material conditions have on their psychologies--suggest to me that the question of individual justification is, in a way, beside the point.

What matters more than whether or not the Kims are justified in doing what they do or whether the Parks are justified in living the kind of lives they live is less important than the question of what kind of society allows for the existence of parasites, and the question of the grounds on which such a society can be justified. These questions are, of course, not new questions (especially to those of us on the left), but it's been a hot minute since I've seen them brought up so forcefully in a popular film. And I'm glad for that.

What I didn't Care for

Perhaps the only thing I really didn't like about the movie is the very last ten minutes. First and foremost, the fact that Kevin survives two massive blows to the back of the head from a thirty pound rock then wakes up in a hospital is absolutely absurd. It seems to me that the only reason he lives is to deliver the narrated anti-climax and, as everyone knows, making x happen to a character because y needs to happen is usually a bad reason for x to happen.

In the same vein, I thought the back and forth letter narration between father and son were a bit too heavy-handed and didactic (not to mention that there was no narration through the rest of the movie which makes this part of the movie stick out).

That being said, I get what the director is going for in showing us Kevin's fantasy and why he included the scene. I understand that the final scene in which the family is reunited is an impossible fantasy that Kevin needs to indulge in in order to go on. Kevin won't get rich, he won't buy the house, and he will never see his father again. This fantasy is both a way of making sense of his life and its direction, and (seemingly) the only source of comfort he has in light of the events of the movie. It allows him to make sense of his life by giving him both an interpretation of what went wrong (he didn't play by the rules! He thought he could get ahead quickly through subterfuge when he should have been working hard to become a millionaire!) and what he must do to set things right (he has to make a plan and stick to it and be perfect!).

This, of course, is just Kevin's return to the neo-liberal capitalist ideology that underwrites and sustains the very system that makes it possible for there to be 'parasites' in society the first place.

The scene is tragic because despite everything that's happened, Kevin simply can't escape this ideology--his suffering has only driven him further into it. And we understand why this is the case. His material conditions prove his father correct--there's no point in making long-term plans if something as simple as a rainstorm can completely destroy your life. However, to accept this and truly live without such long-term plans is, in essence, to live as an alienated impotent entity, simply reacting to the things that one is incapable of changing one way or the other. Arguably, that way of living is hardly worth living at all--it truly is to live opportunistically (like an animal or...a parasite). In such a situation ideology serves to smooth things over and play a conciliatory role: things aren't really what they seem; the material conditions don't make it impossible to live a good life; the world rewards merit, grit, and effort; justice and injustice are ultimately a matter of how individuals relate to one another. Kevin embraces this idea because it allows him to continue living as a human being. In the absence of an alternative way of making sense of things, who could blame him for going in this direction?

All this is to say I understand the importance of this last scene and I think the message conveyed is an important one. Nevertheless, I just didn't like the narrative choice taken to deliver that message--reading it out through a series of letters just felt...I don't know...artless (especially after the equally artless magical revival of the main character).

[The other side of me wants to fill in the other half of the leftist critique: the choice of the poor is not to either deny the reality of their material circumstances and escape to fantasy or to accept that reality and live in misery. One can accept reality and fight to change it. But I'll leave it alone--no movie needs to do everything]