Is Using an AI to Write a College Essay like Using a Calculator to do Math?

On the value of learning to write

I.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about what we do when we teach (or try to teach) students how to write a philosophical essay. These reflections were prompted by two things: first, by a rather dismal display of writing by the students in one of my classes, and second, by the release of AI software like ChatGPT and the implications it has for plagiarism.

When it comes to the former, I take my share of the blame. It’s a poor teacher who blames his students for not learning well enough from him, and I’m ready to concede that if I’m unhappy with the quality of my students’ writing I should have taught them how to write better. However, that won’t be my focus here—at least not directly. Rather, I want to say a little bit about the AI stuff as a way of working through some thoughts about the purpose of a philosophical education.

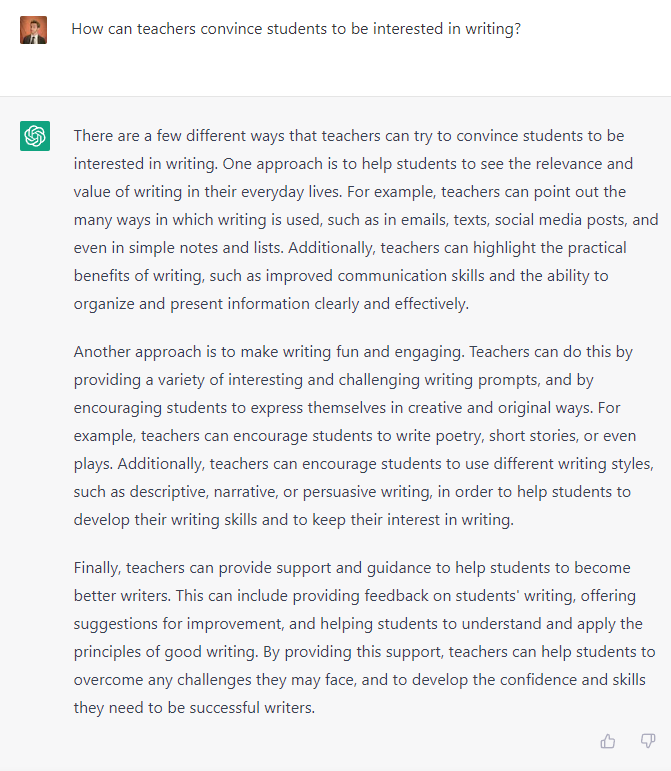

Like many people, I’ve been blown away by how good the ChatGPT AI is at doing things that I would have thought would be impossible to do only a couple of years ago. Admittedly, I’m not on the cutting edge of AI research, so I don’t know how this particular AI model compares to the state of the art, but I am old enough to remember playing around with SmarterChild on AIM in the early 2000s, and, well, these two are nearly incomparable. I’ve had ChatGPT write me a mystery story, turn that story into a screenplay, write a film trailer, create a website promoting the movie, and generate a series of tweets between people arguing about whether the movie will be a flop. I’ve presented it with moral questions and immoral requests (things get really interesting here, but I’ll save that for a different time), and, of course, I’ve had it try to answer some philosophy prompts that I’ve used in my classes.

The results, for the most part, are fascinating. Consider the following prompt (I shamlessly stole from Cameron Buckner): “You are a philosophy student writing an essay in response to the question: "Why does Kripke think that being the teacher of Alexander the Great cannot be the sense (or part of the sense) of 'Aristotle'? Do you think he is correct on this point? Why or why not? Compare the analysis by analogy to a more familiar name of your choice about which the same issues arise.””

And here are the results:

In his book "Naming and Necessity," Saul Kripke argues that the name "Aristotle" refers to a specific individual and that it is not possible for the name to refer to anyone else, even if that person has all the same qualities as Aristotle. In other words, Kripke believes that the reference of a name is fixed, and that it cannot be changed by our beliefs or descriptions about the person in question.

Kripke uses the example of Aristotle being the teacher of Alexander the Great to illustrate his point. Even if we believe that Aristotle was the teacher of Alexander the Great, this belief does not change the reference of the name "Aristotle" to refer to the person who was actually Aristotle. In other words, being the teacher of Alexander the Great cannot be part of the sense (or meaning) of the name "Aristotle," because the reference of the name is fixed and cannot be changed by our beliefs or descriptions.

I think that Kripke is correct on this point. In general, the reference of a name is fixed and cannot be changed by our beliefs or descriptions about the person in question. This is because the reference of a name is determined by the person who first introduced the name and the way in which it was subsequently used in the language community. Our beliefs and descriptions about the person may affect how we use the name, but they do not change its reference.

For example, consider the name "George Washington." Even if we believe that George Washington was the first president of the United States, this belief does not change the reference of the name to refer to someone else. The reference of the name "George Washington" is fixed and cannot be changed by our beliefs or descriptions about the person.

In conclusion, I think that Kripke is correct in his claim that being the teacher of Alexander the Great cannot be part of the sense (or meaning) of the name "Aristotle," because the reference of a name is fixed and cannot be changed by our beliefs or descriptions about the person in question. This is a general principle that applies to all names and the way in which they are used in language

Now, are there problems with this answer? Absolutely—it is repetitive and blatantly begs the question in certain places by just insisting that beliefs and descriptions can’t change the reference of a name.1 Furthermore, it gets some things just wrong. The sentence “Even if we believe that George Washington was the first president of the United States, this belief does not change the reference of the name to refer to someone else” just doesn’t make sense—this is what we believe and it clearly doesn’t explain why the referent doesn’t change.2

But is it passable as a student answer to that prompt? Apart from the fact that it’s a bit on the short side, the answer is, well…yeah. If I were grading this a short question answer on a take home exam, I might correct the mistakes highlighted above, but note that the student did quite well in the first paragraph, that they’re sensitive to the general criticism of the descriptive theory of names, and that they just struggled to put it all together in the final analysis. Given that it’s written in clear English with no grammatical errors, I might also add some bonus points to reward them: B/B+.

Here’s another example from a real prompt I used for my Feminist Philosophy class: “In one of the pieces we read, Amia Srinivasan argues that despite the fact that nobody has a right to sex, there’s something wrong with a society in which different groups of people are systematically not seen as sexually desirable. Is she correct in her assessment? If so, why might a reasonable person disagree with it? If not, what is Srinivasan missing or failing to understand?”

And here’s the response:

Srinivasan's argument is based on the premise that there is something inherently wrong with a society in which certain groups of people are systematically not seen as sexually desirable. While this may be true, it is important to note that there is no inherent "right" to sex, and a person's worth should not be based on their sexual desirability.

A reasonable person might disagree with Srinivasan's assessment for several reasons. First, they might argue that sexual desirability is a subjective concept, and it is impossible to say that any one group of people is systematically not seen as sexually desirable. Second, they might argue that the concept of sexual desirability itself is problematic, as it reinforces harmful stereotypes and reinforces the idea that a person's worth is based on their physical appearance.

Additionally, a reasonable person might argue that Srinivasan is failing to understand the complexities of human sexuality and the various factors that can influence an individual's sexual preferences. For example, some people may not be attracted to certain groups of people due to personal experiences, cultural norms, or other factors. It is important to recognize that these factors can play a role in shaping an individual's sexual preferences, and it is not necessarily fair or accurate to say that a person's lack of attraction to a certain group is due to systematic biases.

Again, is it perfect? No, not quite. But it is definitely something that would receive a pass and which I wouldn’t have clocked as written by an AI. Indeed, the AI tends to make the same kind of mistakes that a student very well might make: it makes reasonable points but fails to elaborate on them, it doesn’t see the tension between the points it raises, it doesn’t explain what it means by certain terms that are important to the argument, and so on. These are precisely the kinds of things that are common in undergraduate writing.

The point is not that the work here is perfect such that it’s impossible to tell an AI generated essay from a real student essay,3 but rather that it's good enough to do the job that we expect it to do.

Now, some of the discourse I’ve seen (online mostly) is centered around the different ways that instructors will need to adapt in order to avoid the supposed deluge of AI generated papers. Some people have committed to eliminating all take-home writing assignments and returning to doing in-class hand-written exams as a means of assessment. Others have tried to come up with more and more creative prompts that can’t be answered by an AI. I wish both groups good luck in their attempts, but I have a feeling this is a losing battle. I think as AIs become better at patching up the things that make them recognizable as such in writing, more and more students will resort to using them in writing their papers. Generally speaking, if the future of pedagogy lies in creating ways to suppress methods of undermining the learning process, then we’ve already lost track of what we’re doing in trying to teach our students how to write.

This, of course, raises the question of what it is we are doing (or trying to do) in teaching students how to write. It is this question that I think matters more than the question of what technology we allow or suppress since the answer to the former question will, to a large degree, determine how we answer the latter.

II.

Consider the following argument:

There have been times in the past in which the advent of a new technology makes learning a particular skill entirely unnecessary. Growing up, we were told that we couldn’t use calculators on math exams because “you won’t have a calculator in your pocket wherever you go, so you’ll need to be able to do this by hand.” That turned out be false: most of us do carry around calculators in our pockets and the number of times I’ve had to do any math that couldn’t be done on my phone are few and far between. Likewise, we were told that each of us would need to learn how to write cursive and would have to practice penmanship so that we could write legibly. That, too, turned out to be false. The only times I have to write by hand is in filling out forms on paper or signing birthday cards; everything else is typed on a computer. The same goes for learning how to drive stick, how to read a printed map, how to plan a trip to Hawaii, and so on. In short, each of these skills has been rendered obsolete by a new advance in technology.

Crucially, however, none of this means that the domains in which new technological advances appear are obsolete. The fact that most people aren’t doing math by hand, don’t have good penmanship, or don’t drive stick, doesn’t mean that mathematics, communication, or driving is therefore obsolete. Far from it, the introduction of calculators, word processors, and automatic transmissions, have made it easier to engage in them because they’ve taken away the rote and repetitive elements of the processes of which they’re a part.

We should consider that the very same phenomenon is happening to the college essay. To fight against the use of AI in this domain and insist that we take every measure to make sure that our students aren’t using it would be like a misguided mathematician insisting that all of their students do their calculations by hand without a calculator, or a computer scientist insisting that their students write their assignments in machine code. It might have some pedagogical value for some people, but on the whole, it is a pointless, Sisyphean task.

This is a bad argument, and the most obvious place to attack it is in the attempt to draw the analogy between essay writing and rote, repetitive work. However, it’s worth considering that there’s something correct about it as well. For example, I think the standard college essay isn’t anything more complicated than rephrasing or repeating what someone else has said about a topic that the student has read about in class. Consider the Kripke example from above: all that is required to answer that question is to take what Kripke says in his lectures/book, summarize it, bring in some objections to it (probably something by Gareth Evans), and then make some hand-wavey general remarks about which view is better. In turn, all that’s required to do those things is that one have (or have access to) good, clear notes and a general outline (both things that I frequently provide for my students as study materials). One doesn’t need to be original, thoughtful, or creative in this process, but simply be able to reproduce a short version of what has already been produced elsewhere. That task, in other words, is a rote one.

Of course, this need not be the case and there can be quite a lot of creativity and originality even in answering a prompt like that. But that would very much be superrogatory when it comes to doing well on such an assignment. In the same sense, one could complete a natural deduction proof in a logic exercise in a new and creative way, but whether a student does that or simply uses the simplest way to get the job done is irrelevant. Would I love to read a new and exciting take on Kripke rather than the same formulaic essay? Of course I would! Should only the essays that say something new and original get a pass? Of course not! Nobody would pass if that was the standard.4

So, as far as it goes, the charge that students are being asked to do something rote and repetitive in writing these essays isn’t baseless. If the analogy is to be broken, it won’t be on those grounds.

A better place to push against the argument seems to be that the writing of such essays aims at something other than the completion of the essay. After all, the goal of learning how to do math by hand is not so that those problems will have been done, but, rather, because, one the one hand, as our teachers wrongfully insisted, we will find ourselves in situations in which we won’t have calculators, or, on the other hand, because having understanding of that process is necessary in order to understand some further bit of mathematics. Setting aside the fact that we do have calculators in our pockets, these claims are correct. We learn how to do math by hand up to a certain point, beyond which we embrace the automation of the rote aspects, offloading it to the calculator to do, so that we can spend our time in other ways. By the time one gets to calculus, for example, graphing calculators are a requirement and, as far as I know, nobody does everything by hand. The aim of teaching students how to do calculations by hand, then, has a practical value in light of the goals one has for the future.

Altering things slightly, we might then say that one should learn how to write the standard college essay because, first, one might have to write something similar in the future without the help of a tool that can automatically do that for them; second, because the content of the essay might be useful in some fashion (and writing is a way of learning content); or third, because writing these essays about these particular things will be relevant for understanding something more important later. But is this correct?

Let me begin with the last suggestion since I think it is right in a limited scope. If one wants to be a professional philosopher or, generally, to write in some academic capacity one must learn how to write these essays because, for better or worse, those essays serve as stepping stones to academic writing. Likewise, there's something correct about the content of some of these essays. Given that one has to have some working repository of knowledge of the field they want to write in, and given that it’s probably true that writing about something helps one generate this repository, learning how to write such essays is of use.5 Both of these things strike me as true, but as useful only if one wants to pursue a certain career. However, the final suggestion that one might be asked to write something similar to a college essay without any aids strikes me as a silly one. I feel confident in saying that nobody will ever have to write college essays after they leave college--including academicians. In fact, I'm rather confident that very few people will even be asked to write anything more complicated than an email once they leave school. Yes, one might occasionally have to put together some kind of grant proposal, or write copy, or something like that, but, with all due respect to copywriters, those are things that can be automated. And even if I’m being entirely unfair here, the point remains that the kind of writing that most ordinary people are likely to encounter in their day-to-day life doesn’t look anything like the college essay, nor is the college essay necessary in order to master that kind of writing.

So, we’re left with something like the following scenario: on the one hand, there is a small group of people for whom writing the college essay is a necessary step towards learning how to write beyond it. Just as the future mathematician learns how to do calculations by hand so that at a certain point they can stop doing those calculations (and let their calculator handle it), so the future academic learns how to write the college essay so that at a certain point they can stop doing that and write something else. On the other hand, there appear to be the vast majority of people for whom such essay writing is neither an end in itself, nor a means to some further end, but just a weird rote and repetitive exercise.

If this picture is accurate, then, the core of the argument presented at the top of this section isn’t that absurd: the college essay is of limited value for only those who plan to continue in academia (and then only as a means to becoming a better writer), and is of very, very little value to anyone else. And if that’s true, then why insist on preserving it? What is lost if we completely give up on the college essay?

III.

There are a couple of preliminary answers to this question. The first falls out of our previous discussion: there are people for whom this practice is necessary. For example, I would be horrified to find out that a graduate student in philosophy wrote all of their undergrad papers using an AI because it would make me very suspicious that they could write at all. Now, that suspicion might be easily dealt in all sorts of manners, but I think there’s something to be said about someone having mastery of some basic skills in the discipline. In the same way that I’d like a structural engineer to be able to do some long division, so I’d like my lawyer to be able to write a five paragraph essay about why it’s not okay to break the law if you really want to.

In a similar vein, given that students don’t always know what they want to do when they enter college, it’s not out of bounds to want and expect them to do some things that would be useful if they were to go in a particular direction, but which might not be useful if they don’t. I might not have gone into philosophy, in which case writing about disjunctivism might not have been useful, but having done what I did, it turned out to have been so.

However, both of these suggestions seem to speak in favor of a finer (self?)selection criteria in schools: if you want to be a chemist, you don’t have to write a single essay in your life; if you want to be an anthropologist, you do.

But I think there’s something more to be said here that, in some respects, tends to shade more romantic than I would generally like it to. In particular, some folks might want to argue that there’s something about being made to do these kinds of exercises that build character or teach better communication skills or something like that. As I’ve suggested, I’m rather skeptical that this is the case. I don’t think that character is necessarily built by doing things that are of limited use, and I think that what makes for good communication is much more contingent on the communication norms of those around us. In other words, I think someone can be an excellent communicator without being able to write a college essay because they know how to talk to the people around them, and, conversely, that someone can write excellent college essays (or professional essays) and be terrible at communicating because they only know how to write a particular way.6 When people tell me that this is the value of learning how to write, I take them to have strayed too far into a kind of romanticism (I think something similar of people who teach philosophy as a series of "tools" in a "toolkit", but that's another matter). To put it short, I don't think that learning to write this particular thing is of value to everyone and that some romantics come very close to thinking that this is the case when they preach for the virtues of good communication practices.

However, I’m perhaps a romantic at heart because I do think that learning how to write—even the standard college essay—helps people think better. This is not necessarily because good writers are good thinkers, but rather because the very act of writing forces people to slow down. Thinking, as it appears to the individual (okay, as it appears to me anyway), is deceptively transparent—one feels oneself jump from one point to the next with the confidence that the steps taken are firm and secure. And in many cases, that’s just not true. I can’t count the number of times that I’ve thought I understood something or that I had a good grasp on it, only to realize that I was completely off-base once I tried to set pen to paper (or, I suppose, fingers to keyboard). What in my head seemed like a clear and coherent line of thinking turned out to be a jumbled mess of suggestive thoughts that lead to nothing. Writing allows one to see when this is the case and to make one aware of the gaps and jumps they’ve made in their thinking and, with help, to rectify them.

This is compatible with the fact that such a process is, at heart, rote, repetitive, and often, annoying. But I think that even when it is, it requires a certain kind of discipline to slow down, structure and explain what’s going on in one’s head. And that, I think is something that is of value even if 1) one never goes into academia; 2) one never writes anything more complicated than an email; 3) the content of what one writes about is never used after the class; and 4) AI becomes so good that it becomes indistinguishable from excellent student papers. This is also where I share the most ground with the romantics: learning to write is good for learning how to communicate with others, but not because the key to good communication is reflected in good writing (consider someone like James Joyce if you’re still skeptical—wonderful writer, but…uh, I wouldn’t say the ideas are easily communicated). Rather, it’s because as a form, writing requires that one slow one’s thinking down and be careful.

It is here, also, that I think the analogy between calculators and AI generated essays is both clearest and where we can most easily diagnose its problem. One might argue that the practice of solving math equations by hand also engenders a kind of discipline of (mathematical) thought that is useful to know. I agree. This is why we first teach students how to discipline their thinking in doing these smaller problems before we allow them to use calculators in doing more complicated kinds of math. The same, I believe is true for writing college essays and becoming disciplined in (verbal) thought. And as long as students do not yet have the mental discipline to structure their thinking in clear ways, then the college essay is of value. If it were true that by the time students came to college they had this skill under wraps, then I think it would be a complete waste of time to force them to write this stuff. In such a world, I would not only welcome to automation of such essays, but would encourage students to use it so that they can get to writing better, more interesting things.

Unfortunately, I don’t think that we’re there. In fact, I think COVID and the two-year online-schooling of most of my students have made them significantly worse at writing than before. This isn’t their fault, of course, but I worry that they will very much take the reasonable argument that they’re being asked to do something that a machine can do as well as they can, that has nothing to do with their interests, and that is boring and painful to do, and let the AI do the work for them. And, of course, in doing that, I worry that they’re simply hurting themselves insofar as they fail to develop this crucial skill of slowing down their thinking. At the end of the day, they’ll make themselves worse for it and it’s our job as educators to prevent that.

IV.

How do we do this? Well, I think we won’t do it by trying to plug in loop-holes in the system or by trying to find prompts that are AI-proof. As I mentioned earlier, I think this is a losing game, and even if an AI can’t answer a certain prompt just yet, I’m sure it will be able to do so in the very near future.

My hope is that we can make better inroads by being explicit and honest with our students about why writing is important and why we’re making them do certain assignments. Maybe it’s naive of me to think this, but I believe that students really do want to learn when they can understand the reason for why doing something is important. Granted, my impression is that they’re too narrow in their conception of what’s important (“will this help me get rich?”), but this isn’t the case with everyone. For example, it seems to me that a vast majority of students are open to the idea that in learning some things they’ll be better able to enjoy different parts of their lives and appreciate things that they took for granted before by picking up certain skills, even if those skills are only orthogonal. In my classes, for example, I often show my students that by learning how to do philosophy they can learn how to appreciate movies better, how to read different characters, and how to isolate different themes. I think something similar can be done with teaching students how to write.

In any case, I’ll leave things here because I can feel myself become less and less careful with my own thoughts and I’m tired.

BONUS: The Bot Weighs in

I didn’t want to leave y’all hanging, so I decided to outsource a fuller answer:

Sounds good to me!

It also does a terrible job if you ask it to elaborate. Here’s what it spat out in response to the following prompt in the same thread: “Elaborate on what you mean when you say that "Our beliefs and descriptions about the person may affect how we use the name, but they do not change its reference."“

”When we use a name to refer to a person, the reference of the name is fixed. This means that the name refers to a specific individual, and it cannot be changed by our beliefs or descriptions about that person. For example, consider the name "George Washington." The reference of this name is fixed and refers to the person who was actually George Washington, regardless of our beliefs or descriptions about him.

However, our beliefs and descriptions about a person can affect how we use the name. For example, if we believe that George Washington was the first president of the United States, we might use the name "George Washington" in a sentence such as "George Washington was the first president of the United States." In this case, our belief about George Washington's occupation affects how we use the name, but it does not change the reference of the name. The name "George Washington" still refers to the same individual, regardless of how we use it in a sentence.

In summary, the reference of a name is fixed and cannot be changed by our beliefs or descriptions about the person in question. However, our beliefs and descriptions can affect how we use the name in language.”

Pretty terrible as far as elaborations go.

It should say something like “Even if we believed that someone else was ‘the first president of the United States’ that wouldn’t mean that ‘George Washington’ refers to that person.”

Funny enough, the major difference is usually in the fact that the AI generated essays are much stronger formally and grammatically than the average student paper, so that one can tell the real thing by virtue of its sloppiness, not because it gets things better.

Some “old school” instructors who pride themselves on their brutal grading practices will drop their monocles indignantly here and insist that maybe some bad teachers don’t have this standard, but they certainly do. Congrats—you’re the hero none of us deserve who has managed to keep a job without succumbing to any of the pressures of grade inflation and student evals. A real Clint Eastwood of the Academy.

I say “probably” because I’m sure I’ve written about things that I have zero recollection of at the moment and which didn’t end up being stored anywhere. I know, for example, that I took a class on early Middle Eastern History and that I wrote papers in that class, but I can’t remember a single thing now.

Have you ever been to a party with a bunch of professional philosophers?