Socialist Reading Series II: Walter Benjamin [Part 3]

Sections IV and V

You already know the deal: read along here.

Section IV

Benjamin begins by stating that every art work is imbedded in some particular tradition.1 Although the work may remain the same physically, the tradition in which it is imbedded may change radically across time: the very same statue of Venus is at one time venerated by the pagan Greeks and, at a later time, condemned by the Medieval Christians. Nevertheless, despite this difference of tradition, both the Ancient Greeks and Medieval Christians still encountered the vase as an object with an aura, and thus, as something with an ineliminable uniqueness. Tradition does not affect the aura, but the fact that the aura of an artwork is and has always been historically imbedded in a tradition does make a difference. Let’s trace that history.

In the beginning (if there was such a time), Benjamin claims, all art works were originally and intimately connected to ritual, and, as such, had a cultic expression. What exactly Benjamin means here by “cult” and “ritual” (and magic) isn’t obvious, but it’s clear that they’re concepts related to the mystical, the spiritual, and the metaphysical. Given what we know about Benjamin’s commitments to historical materialism, his use of the terms is, I believe, best understood as signaling art’s original proximity to mystifying forces. However, this doesn’t mean that Benjamin thinks that there really is stuff like magic or that the realm of religion speaks to something real that’s beyond the everyday world. Far from it, he is simply drawing our attention to the historical relation between art and these mystifying forces that keep us from understanding our real condition. The implicit claim, then, is that there’s a kind of bleeding effect between the two that makes us associate the mystifying force of magic, religion, and the cult with the uniqueness of the aura. In doing so, Benjamin is positioning himself against folks who might think that, for example, art works are special because they provide us with access to a kind of super-sensory world—whether that be a world of magic, religion, or, in its secular guise, beauty. Such people, we might say, are just confused and are bringing in the original value that art had as an expression of the cultic for the value that art works have tout court.

This, again, is another place where it’s clear that Benjamin doesn’t harbor the romantic notions that some people tend to attribute to him. To lament the loss of the aura is, on this diagnosis, to lament the loss of the cultic value which, to reiterate, is just the loss of a mistaken and incidental relation between a mystifying ideology and art objects. Benjamin says this is clearly seen in the Renaissance’s secular cult of beauty, but to understand what he means by this, we have to dip our toes into a bit of aesthetic intellectual history. I promise, I’ll be brief:

Interlude: From Object to Subject to Form and Art for Art’s Sake

Although this is by no means the only way to present the intellectual history of Western Art, we can tell the following story. Traditionally, the starting point of analysis begins by asking what the function of art is, or, to put it another way, what it is that artists do. Whether this is the best or most important question to ask is something I’ll set to the side for the moment since it gets us into some methodological questions that don’t need to concern us right now.2 Regardless, the first plausible answer given to these questions is that the function of art is to capture an accurate representation of the world and its objects, and that what makes someone a (good) artist is that they engage in that kind of practice. On that view, a good painter, for example, is someone who can paint a bunch of grapes to look like real grapes3, a good playwright is someone who can represent social relations realistically, and so on. In other words, good artists are good mimics of what’s real and who provide us with accurate knowledge of the world.4

This way of thinking about things continued until the Renaissance when advances in technology and science present a challenge to it. Roughly, in light of all sorts of new instruments and tools, the idea that, for example, an artist drawing the human body could give us a better understanding of its workings than, say, a biologist armed with a microscope, becomes untenable. If this is true and one learns the truth about the external world by other, scientific processes, then the unique role of art as a source of knowledge and of the artist as serving a certain social and epistemic function is put into jeopardy.5 In response to this threat, the function of art and the artist had to change accordingly and the commitment to mimetic representation had to be dropped. Rather than holding that art helps us better understand the external world, philosophers and artists now held that its purpose was to tell us about the internal world—the world of psychology, of emotion, and feelings that is forever kept apart from the prodding hands of science. Thus, we see artists of the time turn inward, towards romanticism, psychology, and the expression of emotions.6 On this view, good art helped people feel things, and a good artist was somebody who, for example, was able to take what they felt and could accurately convey their feelings to their audience. Or, barring that, someone who could make their audience feel something they—the artist—intended them to feel.

This view of art is still with us today (as are versions of representationalism). However, it, too, faced some significant challenges. Take, for instance, the claim that a good artist is able to take feelings they have and use their craft to transmit those feelings to their audience. This is a plausible claim: Francis Bacon is good artist because, arguably, he was able to capture and produce a strong sense of anxiety and dread in his audience through his paintings. Furthermore, this seems like something he aimed to do with his paintings. If instead of having this effect, his paintings made us laugh or put us at ease, then it seems that Bacon would have failed in some significant way. The same, of course, is true in other fields. Part of what makes Tommy Wisseau such a bad film director (and writer, and producer) is the fact that he intended to make a gritty drama about betrayal with The Room, and instead ended up making something bizarre and, really, really funny.

Although plausible, it’s worth noting how much of the view hangs on the particular mental states of the artist and the audience. Suppose, for example, that we find Bacon’s diaries and discover that he neither felt any emotion of dread or anxiety when making his paintings, nor did he have any intentions of conveying such feelings to his audience. Does it follow, then, that Bacon is a worse artist because of that? Should his paintings be considered bad by that virtue?

(Pictured: Figure with Meat, 1954)

The answer seems to be no. Rather, it seems reasonable to say that if his paintings are good it is such because of what they are—because of certain facts about them— rather than because of their relation to whatever their author felt while making them or whatever they was intended to do. But if that’s true, then it’s hard to see how (good) art could be a reflection of the inner world any more than it could be a reflection of the outer world. It appears, that the function and value of art is, in some important sense autonomous and independent from both its subject matter (whether it represents something accurately, for example) and from its creator (what the artist intends).

So, what is the function of art? What are artists supposed to do? The answer: nothing—the purpose and value of art is simply to be art (l’art pour l’art), or, in more sophisticated versions, to present significant form divorced from any subject matter or internal state of the artist.7 Once this is accepted, purely abstract art as an object of analysis becomes possible and, if we’re being super charitable, art can be freed from convention and tradition.

The overarching historical transition, then, can be pithily stated as one from external object, to internal subject, to pure form.

In any case, this is more or less how many people view art today, often with a kind of post-modern addition of various different elements from different traditions can all be mixed in together. (My uncharitable summary of post-modernism: “Whatever theory or ideology you have: Yes, all that, but maybe none of it”)

Interlude over! (See, it wasn’t that bad—you’re already reading an essay on art anyway!)

I believe it’s a very compressed version of this history that Benjamin is tracing out in the bulk of the first paragraph of this section, though much quicker than I did in the few paragraphs above and with an emphasis on the attempt of art and artists to remain close to ritual. Thus, we see him telling us that the secular cult of beauty develops as a response to the intellectual, material, and technological changes brought about by the Renaissance, and that this was an attempt to preserve the ritual connection that art originally had. This part of the story maps onto the turn away from representationalism which is completed once photography arrives on the scene as “the first truly revolutionary means of production…simultaneously with the rise of socialism, art sense the approaching crisis which has become evident a century later.” The art world then responds to this crisis by developing the doctrine of “art for art’s sake” (l’art pour l’art ), once again, in an attempt to retain the connection between art and ritual.

This [response] gave rise to what might be called a negative theology in the form of the idea of ‘pure’ art, which not only denied any social function of art but also any categorizing by subject matter.

The development of this “theology of art” maps onto the turn away from the internal sphere towards the purely formal: the art doesn’t have do anything or be about anything. It’s just something special, ephemeral, and other-worldly—pure and grasped solely by a refined aesthetic intuition that takes us closer to beauty (whose intuition? Hmmm…certainly not yours if you don’t have it…).

Okay, we’ve covered a lot of ground, so it’s worth bringing things back into focus.

The purpose of this entire discourse—this brief tracing of art history—is twofold: first, it serves to draw the reader’s attention to the fact that art has a particular history that grounds it in all this magical stuff that Marxists generally want to dispose with as explanations for historical phenomena. To reiterate for the umpteenth time, this is just another instance of Benjamin being a Good Marxist and a Good Historical Materialist working in that tradition. Incidentally, making this history explicit also allows us to screen off some potential objections: if, for example, you think of ritual, magic, God, Beauty, etc. as real things and not as mystifications of historical material processes, then you can be certain that your disagreement with Benjamin goes much deeper and meets him at a different level than if you don’t believe this.

If, however, you accept that the original role of art is deeply imbedded in ritual, if you think that its relation to such ritual doesn’t speak for its value or function but is only another mystifying holdover from an earlier time, and if you can see that contemporary ways of looking at art (viz., l’art pour l’art) are just further permutations of this relation, then Benjamin has more to offer you.

Namely—and this is the second purpose of this discourse—it allows you to catch a glimpse at the emancipatory power that mechanical reproduction of art has. Here’s Benjamin in his own words:

For the first time in world history, mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual. To an even greater degree the work of art reproduced becomes to work of art designed for reproducibility. From a photographic negative, for example, one can make any number of prints; to ask for the ‘authentic’ print makes no sense. But the instant the criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production, the total function of art is reversed. Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice—politics.

This is a very important passage that we’ll return to later, but I just want to highlight a couple of things for the moment. First, I want to stress the general thesis that is being developed across these sections: because art has historically been used for ritual, it has developed a strong association—a parasitic relationship—between the aura of art and ritual that gives the impression that the aura itself is magical; mechanical reproduction destroys the very notion of authenticity by destroying its aura, and, in turn, destroys its link to ritual; and by doing this, it reverses the function of art and allows for its emancipatory potential.

The point of reversal is an especially interesting one that we should keep an eye on through the essay, but, as a starting point, it immediately raises the question: what was the function of art such that it is now reversed? The answer to this question is implicit in the quote above: until this point, art’s function (intentionally or not) was to mystify and convince people that there is a world beyond their control. The ritual, cultic world is a world inhabited by powers that we are not in charge of, and is serviced by a group of people who commune with that world, who perform its rites, who know its secrets, and who follow its rules. In other words, it is a world with a bounded inner core of specialists that implies the existence of an outer core of people who do not and cannot engage with it, who must not be allowed in, and who inhabit the ordinary, mundane, material world. By destroying the mystifying function of art with mechanical reproduction—by freeing it from its “parasitical dependence on ritual”—Benjamin thinks we are finally in a position to rid ourselves of this illusion, and, crucially, to see that world as one in which we can do politics. We can, for example, ask who is barred from participating in art and why they’re barred from it. Once we see that this is how art operates, we are also in a position to see that this is how the entire world operates as well. If art can be demystified and shown to be a matter of what we, the ordinary people of the world make of it, then so can the economy.

Finally, it’s also worth stressing just how different Benjamin’s emancipatory vision is from the emancipatory vision of “pure” art that I mentioned earlier. On this, perhaps more standard view, the emancipation comes from being freed from the internal demands and ideas of the art world itself: because the artist is no longer forced to stick to a particular tradition or style (say, depictions of Christ, realistic still-life painting, flat Byzantine mosaics, or whatever) they are free to do whatever they want to do. At the same time, this move places a certain authority on the part of the consumer who is likewise freed from having to engage with the art in its particular context or tradition.8 In other words, this emancipatory picture is one of an opening up of ideas that, as many people think, goes hand in hand of a broader opening up of all sorts of thought, and which simply comes with modernity, rationalism, democratization, and, of course, a liberalized economy.

Benjamin’s picture of emancipation is very different. It, too, acknowledges a break from a traditional way of thinking about art, but, crucially, that break is not driven by a fundamental change in ideas, but, of course, by a change in the means of its (re)production. What mechanical reproduction can free us from is the way art has been parasitically bound to ritual—to the mystical and magical things that obscure the true relations in the world—and not simply from the specific ideas about what art can and can’t be. The former is a much broader phenomenon than the latter and it can be seen by the fact that, as Benjamin has pointed out, one can still be deep in the throes of mysticism while being freed from a particular tradition. Indeed, the charge implicit in his criticism of the l’art pour l’art movement as a theology of art is precisely that it still mystifies because it is unable to break the link with ritual. This difference is key in understanding what follows.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. (How did two paragraphs spawn this whole thing? This reading series is getting out of hand…)

Section V

This section presents us with the very important distinction between the cult value and exhibition value of art objects. The cult value of an art object is to be understood in terms of the object’s relation to some specific cultic, animist, or pagan spiritual practices. In other words, there are certain art objects whose value depends on it being a part of such a ritual and not because it could be seen by people. Thus:

The elk portrayed by the man of the Stone Age on the walls of his cave was an instrument of magic. He did expose it to his fellow men, but in the main it was meant for the spirits.

This kind of value is still to be found in certain religious contexts:

Today the cult value would seem to demand that the work of art remain hidden. Certain statues of gods are accessible only to the priest in the cella;9 certain Madonnas remain covered nearly all year round; certain sculptures on medieval cathedrals are invisible to the spectator on ground level.

Now, it’s clear that Benjamin is making some substantial empirical claims, the validity of which I’m not in a position to assess. Frankly, I don’t know if it’s true that cave paintings were instruments of magic and I’m not convinced that Benjamin knew either. I’m sure that there may have been very complex reasons for why “the man of the Stone Age” would have painted elk on the walls of his cave, some of which might not reduce to a belief in magic or communing with the spirits (maybe he just liked elk!).

Modern anthropologists, archeologists, and art historians would be better positioned to answer this particular question and it’s very possible that Benjamin is just wrong about cave paintings. Nevertheless, it’s important to note the scope and strength of his claim. On the one hand, it appears to be an important one since it’s an important part of the history that Benjamin wants to tell about the development of art. On the other hand, however, the particular specifics are not terribly important because they’re only meant to illustrate what it means for an art work to have a cult value. If we can make sense of the person who paints elk on the walls of their cave not to show others what they’ve done, but as part of some ritual, then we have a grasp of what Benjamin has in mind. Furthermore, as his Christian examples point out, we know that people have made art works precisely for this purpose, so it’s not that big of a stretch to imagine that people did so in the past. And, of course, we know from the archeological record that even if cave paintings in particular weren’t involved in ritual, there are plenty of other cases in which art and ritual go hand-in-hand (think ceremonial daggers and whatnot).

From that perspective, the point is made. But let’s not let Benjamin off the hook just yet. As I mentioned, the kinds of claims he makes here are important because they’re not supposed to just tell a hypothetical story of how art develops, but its actual story. To put the point more forcefully, Benjamin is in the process of telling us how art begins with an emphasis on the cultic value and how changes in the means of (re)production cause it to shift to the exhibition value which we see today. If it’s simply not true that art begins that way, then a different story must be told. And, again, I’m not sure whether Benjamin’s story is correct.10

In any case, the story continues:

With the emancipation of the various art practices from ritual go increasing opportunities for the exhibition of their products. It is easier to exhibit a portrait bust that can be sent here and there than to exhibit the statue of a divinity that has its fixed place in the interior of a temple. The same holds for the painting as against the mosaic or fresco that preceded it.

Here’s a wonderful illustration of how the change in art (re)production leads to change in how people relate to art. Originally, again, art works are tied to their cultic value: here is a statue for the Temple of Aphrodite—it rests in in that temple and one must go to that temple to see it; there is a Byzantine mosaic of Christ and the Disciples, built into the wall of the basilica; etc. Those are fixed entities that have a definite place because of their relation to ritual; they exhibit a primarily cultic value. As art becomes free from this grip (it’s unclear how this emancipation proceeds, but it’s reasonable to say that for Benjamin it, too, is driven by certain material forces), it becomes possible to make individual portraits on canvas, little busts of so-and-so, etc.11 And because there are new ways of producing and transporting art works, they are able to circulate and, thus, to have an exhibition value.

Okay, but what is the exhibition value of a work? Simply put, the exhibition value of a work of art is to be understood in contrast with the cultic value: whereas cultic value is found in the exclusivity of access to the work—in the ways in which it is hidden from view because of its relation to magic—the exhibition value is to be found in its accessibility to the masses.

I admit, why this should be the case—why exhibition value should be a value at all—is still opaque to me. However, the general idea is an illustration of Hegel’s/Marx’s claim that “merely quantitative differences beyond a certain point pass into qualitative changes.”12 The merely quantitative difference with respect to art is quite literally how many reproductions can be made of the artwork; the qualitative change is the change in the nature of the work itself. To put it in even simpler terms: when there is only one copy of a work of art that has its bespoke place in the mystified world of ritual from which I am kept out, then I relate to that art work in one way: I present myself before it, I subject myself to its aura, I enter its magical world. As more and more copies can be made of that very same object, it changes and my relationship to it changes as well: now it enters my house, now it’s available on my phone, it submits to me rather than the other way around. Before it can be reproduced in this way, it has one function: to aid magic. Once it can be reproduced this way it has a new function: to please me. These are not the same functions.

We see Benjamin making this point as follows:

With the different methods of technical reproduction of a work of art, its fitness for exhibition increased to the such an extent that the qualitative shift between its two poles turned into a qualitative transformation of its nature.

He continues:

This is comparable to the situation of the work of art in prehistoric times when, by the absolute emphasis on its cult value, it was, first and foremost, an instrument of magic. Only later did it come to be recognized as a work of art. In the same way today, by the absolute emphasis on its exhibition value the work of art becomes a creation with entirely new functions, among which the on we are conscious of, the artistic function, may be recognized as incidental.

This is important, once again, for seeing the emancipatory vision Benjamin has in mind. Just as previously, because of the emphasis on the special place that a work of art has in relation to ritual, a work may not have been seen as art,13 so, too, what may be primarily seen as having the function of art today may really have a different function. What function, you ask? Politics, of course. And where should we look for this new function? In the art form that is most reproducible and hence, the most on the way towards changing its qualitative nature: photography and film.

I want to make one final point that I couldn’t quite figure out how to fit into the overall narrative, but which I found myself struggling with as I was writing. Namely, it’s important to note that the cultic and exhibition values that Benjamin talks about are not exclusive in the sense that something either had exhibition value or cult value. It’s quite clear that what he’s talking about are accents or emphases of value with different works, but that can be easy to miss. Given that we’re talking about emphases, there are clearly going to be cases in the middle where these two values are both on display. A good example of this is the Mona Lisa.

According to this Guardian article from 2019, an estimated 30,000 people come in daily just to see this painting and take a selfie in front of it. Clearly, it seems that the painting has some exhibition value, and indeed, I suspect that one of the reasons it is so popular is because one the reasons to see the Mona Lisa is to have seen it. At the same time, however, the painting itself doesn’t move (much)—one still has to meet it in Paris, behind its bulletproof covering, flanked by security. It’s not much of a stretch to say that the “ritual” to which it belongs is that of “going to Paris” with this being one of the stations one passes through in that ritual. Furthermore, people are still very much enamored by this ritual and, in particular, to the aura that the painting exhibits—it’s not enough for me to pull up the painting on my phone and tell you that it looks exactly the same and unlike at the museum, you can spend as much time looking at it in as great detail as you want without any French person telling you to move along. You won’t buy it because you’ll want to be in its presence.

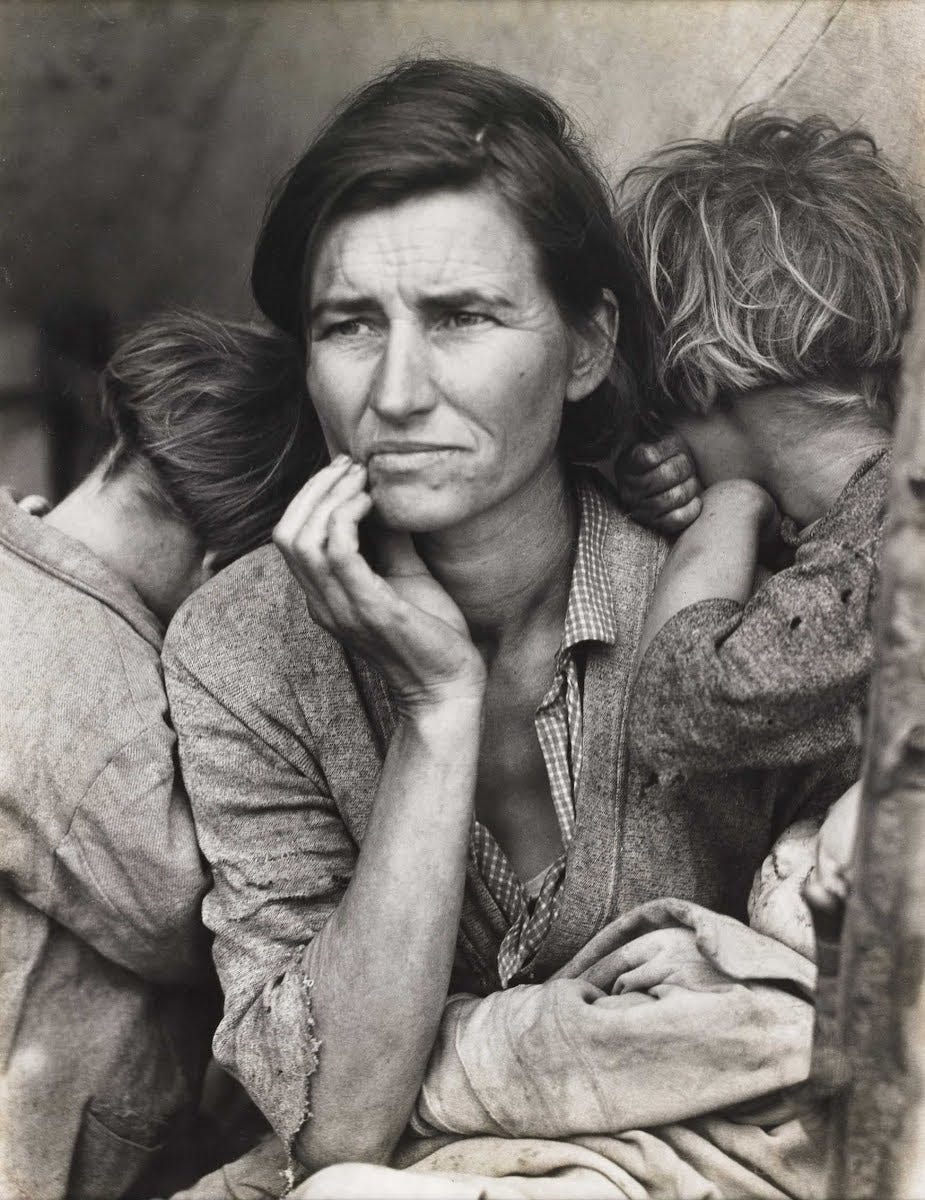

Why do I bring this up? Because, given some of the discussion of forgeries and reproductions in the previous sections, and given the way we tend to think about art, the examples that might immediately spring to mind (and the examples I’ve used in these discussions for the very same purpose) are of canvas paintings and statues. These are, of course, art works, so they are in the scope of Benjamin’s analysis. However, the emancipatory vision that Benjamin has is not about the reproduction of those works of art, but, I believe, of those art practices which produce works whose entire function is to be reproduced. This is why the vast majority of discussion from now on will focus on photography and especially film and won’t be about, for example, how reproductive technologies can help us make fantastic forgeries of the Masters. Those works, recall, still have an aura and a history against which authenticity is determined and preserved. By contrast, films and photographs do not. From jump, they are things made to be reproduced: there is no “original” Taxi Driver or Migrant Mother (see below), only different prints of it.

Keep all this in mind or else things tend to get confusing.

I had to look it up, “imbedded” is fine. It’s just a different spelling of “embedded.” A translation quirk.

I suspect that this way of looking at the matter is an artifact from Plato’s methodology in which different crafts are defined by the different ends they aim towards.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeuxis_(painter)

Indeed, it is on this basis that Plato mounts his famous attack on the arts in the Republic: artists deal in appearances, but quite clearly, to make a convincing appearance of something doesn’t require knowing anything about the truth of that thing. A person might be able to draw a very convincing picture of a Ferrari, for example, without knowing anything about how the engine works, how it was made, or anything like that. Yet, at the same time, artists often present themselves as giving us access to the truth—as holding up a mirror to the world through which we can see it more accurately. Crucially, for those who do not know any better, such presentations might be effective, and some people might actually end up believing what is presented as appearance to be the truth. Since it would be imprudent to take that risk in the ideal city, Plato banishes all imitative art from its borders.

As with all things, Aristotle challenges Plato’s account by reminding us that people aren’t as dumb as Plato thinks they are. He’s right, but interestingly, he doesn’t give up the representationalist paradigm that Plato accepts—he just broadens its scope a bit.

The proverbial nail on the coffin of the pure representationalist was, of course, the advent of photography. In the best scenario, the most perfect human artist simply does what any ordinary camera can do. Our terminology reflects this: such artists are said to make “photorealistic” art.

Here, again, Plato and Aristotle’s methodologies are in the background: if what’s supposed to set craft A from any other craft is having end x, but if it turns out that craft B also aims at x and can achieve it better, then, well, our initial analysis of craft A is not good enough.

Leo Tolstoy’s “What is Art?” is probably the clearest expression of this view.

This is a very rough version of Clive Bell’s view and he’s the one who coined the term “significant form.” What’s significant form? Uh…well, that which good art has that is intuited by someone who knows art real well. You don’t recognize it? Hmmm…you must not know enough about art—better ask an art critic.

This dual movement is important for Benjamin as well since he also thinks that the shift to mechanical reproduction shifts the power in the hands of the people. In that respect, Benjamin isn’t entire disagreeing with the phenomenon that this alternative emancipatory vision presents, but the places in which they do disagree are significant enough. I mention this only to highlight another feature of good Marxist analysis (on my view anyway): namely, it doesn’t deny or try to explain away important phenomena, but rather gives them alternative analyses. In this case, for example, what drives the shift isn’t the change of ideas (“we thought that art had to be such-and-such, but it turns out it can be anything! Now that you’re freed from that idea, you’re free to enjoy anything that pleases you, consumer!”), but rather points out how these very shifts in ideas themselves are rooted in changes in material forces.

I had to look this up: a cella is “the inner area of an ancient temple, especially one housing the hidden cult image in a Greek or Roman temple.”

I’m relegating this discussion to a footnote which, as everyone knows, is where you put things that nobody’s going to read. Psychopaths use endnotes. In any case, one reason why we might be suspicious of Benjamin’s claim is because there might be significant questions about what we interpret as art works from our modern perspective. I think it’s pretty well-established that for a very long time people didn’t look at the kinds of everyday objects that women used or made as art because of they were primarily objects of utility (and, of course, because of sexism). If our analysis of the beginning of art already assumes that art must have some specific central purpose to count as such, then it wouldn’t be surprising that in looking back we should find art primarily in locations like temples, alters and whatnot. Another reason to be suspicious might be that only certain kinds of art objects would survive from antiquity—namely, those made out of durable materials in places that were relatively preserved for some reason or another. To put it another way, the kind of art that you or I might make might not survive for another 5000 years (indeed, they might not survive the next time we move house), but Michelangelo’s David might. If future archeologists were to look at just what was preserved, they might draw the conclusion that the creation of art was an exclusively museum-related affair when that’s just not true. In both cases, if our analysis of the origins of art already has baked into it the condition that we’re only going to find art in places of ritual and magic, then it’s not a surprise that we should find art in those places.

Among some of the factors that might make a difference here might be the sources of patronage for the arts, the materials needed to make art, who gets to be educated in the arts, and so on. All of these are, of course, ultimately a function of the modes of production and who controls the means of production—there’s no Renaissance art without a burgeoning Italian merchant class that can afford to be patrons to a bunch of artists to paint for them.

Marx says this in Ch. 11 of Volume 1 of Capital where he describes it as a general law that he attributes to Hegel in his “Science of Logic.” Pick your poison.

I want to draw the reader’s attention to footnote 10 above as a kind of illustration of the same phenomenon in reverse. At one point, women’s work is not seen as art because it is seen as having a certain quantitative relationship (i.e., utility). This, in turn is due to having the sheer quantity of the “crafts” they make and, crucially, the fact that this keeps them from exhibiting their cultic value. After all, how can something that is used by a bunch of people or is seen by a bunch of people be art? Now, throw those same artifacts in a museum, surround them with heavy glass, lean in on their aura, and the fact that they are so rare and singular, and suddenly they transform into High Art! What magic! Lest you think that we’re somehow advanced, just remember that this is not the attitude that anyone has when they go to craft fair. Don’t these people know that the bejeweled crosses hawked by mee-maws at the DFW Craftmaniacs are the art objects of the future?!