Socialist Reading Series III: Georg Lukacs' "Class Consciousness"

Introduction: What is Class?

I first read Lukacs (pronounced LOO-katch) about four years ago, perhaps a little bit after reading my first bits of Lenin, but certainly long before I felt that I had really understood any of the latter’s philosophy.1 I knew that Lukacs was supposed to be one of the best interpreters of Lenin, but what I mostly remember from my first encounter with his work is that it was both painful to read and almost impossible to understand. Recently, however, I had reason to revisit some of Lukacs’ work and was surprised to discover that I could not only understand what he was saying, but that it made a lot of sense! So, I thought working through one of his essays might make for a good—and hopefully short—socialist reading series entry. The plan is to walk through “Class Consciousness,” and to explain what’s going on there to the best of my abilities, making the text a little less painful, and a little more accessible.

As always, it’s important to note that like the other works I’ve covered in this series, this is not a piece of academic or scholarly work—I’m not consulting the original Hungarian, nor am I reading secondary interpretive sources. Everything that follows is simply intended to use my knowledge of Marxism and philosophy to make sense of a text that might seem intimidating, but which I believe has a ton to offer to leftists. If at least one person feels that they have a firmer grasp on the topic as a result of this, then I’ll feel pretty good.

And finally, although I’ll be summarizing and commenting on the essay, it’s always best to read the original beforehand (or at least read it along) so that you have a sense of what’s going on in the text independently of what I’m saying about it. Thankfully, the good people at Marxists.org provide a free copy of the text which you can find here.2 Let’s get started!

Introduction

The introduction to the essay is brief but important as it lays out the main questions that Lukacs will attempt to answer in the remainder of this essay. As with all such introductions, we can use the questions to not only orient ourselves around the text, but to hold the author accountable to the task they set for themselves.

Before we do that, however, we have to talk about class.

Lukacs says: “In Marxism the division of society into classes is determined by position within the process of production.” Understanding this claim is crucial because the questions that Lukacs will raise about class and class consciousness follow from understanding it, so it’s worth spending some time to unpack it. Please, bear with me.

We can start by noting that ‘class’ is a social category. It is a term concerned with relations between (groups of) people—Adam did not belong to a class (at least not until Eve shows up), and while the last person on Earth may have been part of a class until a certain point in time, once they are alone it makes no more sense to say that they are a part of a class than it does to call them a philanthropist or a socialite. This much is clear. However, while most people will acknowledge that class is a social category, they tend to think of it as one that is constructed on the basis of a loose set of shared individual economic, cultural, and psychological characteristics. Let me explain.

To be working class in this sense is, of course, to be poor—perhaps uncomfortably so. But it is also to speak with a regional accent, to dress in low-quality clothes, to be superstitious or uncritically religious, and, generally, to be uneducated, uncultured, and bigoted. Working class people don’t care for opera, understand the subtle genius of Tarkovsky, or delight in reading Plutarch because of the kind of psychology they have; they drink cheep liquor, eat unhealthy food, curse and spit and are loud and vulgar and sexual because that’s just what they are as individuals. Indeed, it is often these latter (supposed) cultural, psychological, and sociological facts that are employed to explain the poverty associated with the working class. It is because working class people are so psychologically and culturally impoverished that they are therefore unable to restrain their immediate impulses, delay gratification, and save enough money to improve their material condition.

It is this cluster of individual traits, shared by others that binds them to the working class. In turn, even when class is seen as an economic matter, it is seen as downstream from the virtues and vices of its individual members.

The same logic is extended to the upper classes. Apart from their income, it is their cultural, sociological, and psychological virtues that not only allows for, but also makes it right that they should occupy their given space in society. It is middle class’s prudence, self-discipline, respectful appearance, and hard-work that earns them the income necessary to buy a house in the suburbs, take vacations, and buy health insurance.3 Likewise, it is the entrepreneurial risk-taking spirit, pedigreed upbringing, wise investment, and undeterred commitment to excellence of the upper class that secures its members their private jets, luxury yachts, and massive returns on capital gains.

I don’t want to overstate the matter here. There are plenty of people who readily recognize that there are individuals who defy the stereotypes of their class. Everyone knows that there are, for example, working class people who enjoy Tosca as well as ultra-wealthy idlers who do nothing but live off the fat of their inheritance.

Plenty of people will also acknowledge that there are systemic reasons for these anomalies such as unreasonable barriers to entry for certain professional avenues, or exceptionally permissive tax codes that allow the wealthy to hoard. But, on the whole, such exceptions are seen as anomalous precisely to the extent that they are a mismatch between an individual’s traits and talents, and the class to which they belong. The problem seen as such isn’t in the existence of classes, but in their rigidity. The solution to such anomalies, then, is seen as a matter of finding out how to most equitably sort people in the right class based on their traits, and not, for example, to abolish classes all together. Indeed, the very notion of class abolition seems as an absurdity from this perspective because it seems tantamount to abolishing the very concept of categorizing. On this understanding of the term, abolishing class to end economic oppression is tantamount to the suggestion of abolishing race or gender by pretending that there are no phenotypical differences between people—you can try to do that, but people will just find some way of sorting themselves out “naturally” by their differences.

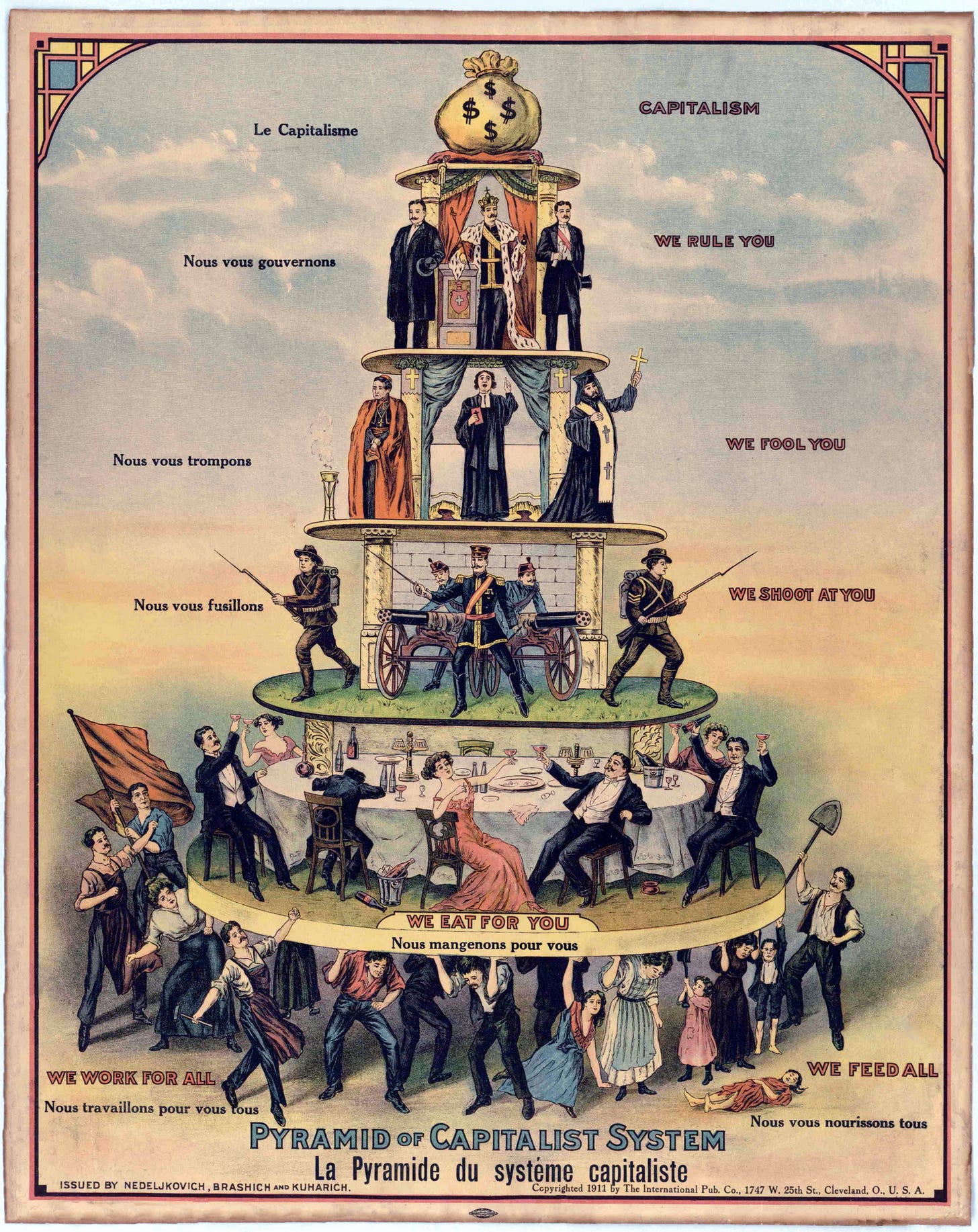

In any case, this is not how class is understood in Marxian terms. Marxists begin their analysis of class not by looking at the traits of individuals which “naturally” lump people into categories, but by looking at society as a whole. Starting there, we can note a couple of things.

First, regardless of its composition, society is something that extends across time and its continuation literally depends on the things that allow it to reproduce itself from one day to the next (e.g., food, clothing, shelter, medicine, transportation, etc.). If society cannot reproduce itself, it will collapse.

Second, the things in question necessary for the reproduction of society don’t come ready-made like manna from heaven, but are always the result of concrete applications of labor in relation to nature—wood must be chopped down, planks must be treated, furniture assembled, crops watered, cloth woven, and so on.

And third, this concrete application of labor is and must always be done by some group of people or other if it is going to be done at all.4 A society in which no labor is done by anyone is a society in which no food is produced, and is also a society that will not be around for very long. Thus, it follows that the (re)production of society always depends on settling the question—through discussion, negotiation, or, most often, through the naked use of violence—of who performs that labor, when, and to what end.

Classes are defined in terms of how those questions are settled.

Consequently, in Marxist terms, the working class is not defined by the culture or psychology of its members, but by the way in which these questions have been settled, and, more specifically, how they have been settled since around the 16th century. The system we call capitalism is just one particular way of settling them.

The working class is that group of people that must labor and which depends on selling its labor power as a commodity in order to survive.5 It must do this for the simple reason that those who make up the working class have no other means of feeding, clothing, and housing themselves, given that they do not own the means by which food, clothing, and shelter are produced.6

They do not own the means necessary to produce these things—the factories, machines, land, etc., or what Marxists call “the means of production”—because, for historical reasons, they are solely in the hands of a different group which, through its control of the state (and the latter’s monopoly on violence),7 also has complete rights to the profits that they may generate. And since this this latter group stands in a different relation to the production process, it forms a different class: we call it the owner class, or, in Marxist terms, the bourgeoisie.

Thus, what places an individual in a particular class is not any individual traits that they possess, nor is it strictly their salary—after all, Mark Zuckerberg only takes a salary of $1 at Meta!8—but rather where they stand in relation to the process of production. If you have to sell your labor power in order to survive, then you’re working class; if you can survive on passive income because you own what society needs for its reproduction, you’re bourgeois.

It goes without saying that much (much!) more can be said about class. I can’t pretend that the two ways I’ve described here are the only ways to think about the matter, and although I’m clearly not impartial about my preference, I also don’t take myself to have given an argument for why one should accept the Marxist version.9 Such arguments exist, but I’m not making them here. Instead my goal has been to illustrate what Lukacs already takes his Marxist audience to assume about class by contrasting it with a version that, even if not ubiquitous, is familiar enough to draw a distinction.

And with all that in mind, we are finally ready to get to Lucaks’ questions about class consciousness.

Given this Marxian use of the term ‘class’, the first question that arises is: “how are we to understand class consciousness (in theory)?” Why is this a relevant question? Well, if ‘consciousness’ is a psychological category that applies to individuals, and ‘class’ in the Marxian sense is neither a psychological category, nor one that applies to individuals, then it’s not clear what '“class consciousness” even means. At best, it may be something obscure; at worst, it might be a kind of category error (something like “rock sexuality” or “horse politics”). Unless it can be shown that class consciousness does not involve some kind of fundamental inconsistency in theory, it is a useless concept.

But this isn’t enough. According to Marxist theory, class consciousness is supposed to be crucial to the waging of class struggle and the bringing about of revolution. That is, it is supposed to have a practical implication for political action. However, it’s not clear how class consciousness as defined is supposed to do this. It’s easy enough to understand how a certain kind of individual consciousness can guide an individual’s actions if we (rightly) believe that there’s a connection between how people think and what they do. However, if it is once again acknowledged that class consciousness is not a psychological category—if it’s not “the thoughts of the class”—then how that consciousness can affect action becomes oblique. Hence, the second question to answer is: “what is the (practical) function of class consciousness, so understood, in the context of class struggle?”

Third, we can ask “is the problem of class consciousness a ‘general’ sociological problem or does it mean one thing for the proletariat and another for every other class to have emerged hitherto?” We can understand this question as follows. Given that classes are defined in relation to their role in the production process, and given that those relations have not always been those of capitalist owner and proletarian worker, it follows that there have also been different classes.10 However, it remains an open question whether class consciousness can be applied to those classes, or whether it only applies to the working class under capitalism. In other words, it remains open whether class consciousness is a concept that can only be uniquely applied to the working class because of specific historical developments, or, as Lukacs puts it, a “‘general’ sociological problem.”11

Finally, we can also ask “is class consciousness homogenous in nature and function or can we discern different gradations and levels in it? And if so, what are the practical implications for the class struggle of the proletariat?” In other words, is it possible for the working class to have a little class consciousness (as a treat), or is it an all-or-nothing thing? Obviously, different strategies follow depending on how this question is answered. If, for example, class consciousness comes in different gradations, and if class consciousness is indeed important to the revolution, then it may be possible to approach the matter incrementally. If, however, class consciousness is an all-or-nothing thing that must be achieved all at once, then incrementalism will not work (or, to the extent that it could work, it would be different in nature).

These are the questions that we’ll be trying to answer in the following sections.

The extent to which I failed to understand Lenin properly is apparent in the first Socialist Reading Series I did which I still available to read, warts and all.

Unless otherwise specified, all quotes are from the section under discussion, so I won’t be doing any footnote citations.

And how could it be otherwise? To argue to the contrary is tantamount to arguing that limited good things that we have to distribute should be given to people who would squander them!

I’m unsure of what to make of something like the suggestion that this is not a matter of necessity and that it would be possible for a society to reproduce itself entirely through automated labor. It seems to me that we’re either talking about a society in which most labor is done by robots but those robots are still maintained by human labor—in which case we are still talking about a class society in which the working class is just made up entirely of mechanics and engineers who do that maintenance—or we’re talking about something like autonomous, self-maintaining intelligent robots with absolutely no input from humans, in which case we’re just talking about a working class whose membership is entirely made by such robots. In either case, class divisions would still persist, but what would obscure that fact would be either the assumed invisibility of the mechanics and engineers, or the firm commitment that intelligent machines cannot be exploited. Tough sell in either case if you ask me. In other words, don’t bet the farm on AI leading you to a class-less utopia.

Labor power = the capacity to labor; labor = the actual application of that capacity

The denial of the sociality of reproduction of society is alive and well in both the fantasy of the frontiersman, who relies on nobody but his own gumption, in the modern day phenomenon of the prepper, and, in its more moderate guise, in the form of the small-government conservative who pulls himself by his bootstraps. Each of these archetypes is, of course, deep in the throes of delusion and none of them have, or, indeed, could exist without socialized reproduction.

One can easily see why Lenin is so focused on the seizure of state power as the first means of ending class society if one looks at things this way.

Lol https://www.cnbctv18.com/business/mark-zuckerbergs-base-salary-is-1-but-other-income-is-24-4-million-19401884.htm

For example, one can reasonably say the two ways of thinking about class are a matter of methodological preference: some people prefer to start with the individual, others prefer to start with the whole. If that’s the case, then some further set of arguments must be made for why one methodological choice is better than the other.

For example, peasants and feudal lords, or slaves and masters.

No, I don’t know why he calls it a “problem”

Found this very clear and helpful. Also: that vest.