Socialist Reading Series III: Georg Lukacs' "Class Consciousness" [Part 4]

Section 1 Part C: Fetishism, 'false' consciousness, and a definition

Part B here; Lukacs’ text here

There’s been a big delay between Part 3 and this part because I got married in October (woo!) and then I just plum didn’t feel like writing (boo!) The two events were not causally connected. Anyway, back into the fray!

We ended the last post on a dilemma, one horn of which makes “the objects of history appear as the objects of immutable, eternal laws of nature,” and the other horn of which transforms history “into the irrational rule of blind forces.” Neither of these two options proved to be satisfactory in solving the “problem of history,” which, recall, arises when we attempt to treat history as a social science.1

Lukacs now tells us that Marx resolves this dilemma by showing it to be an illusion. He says:

For in this historiography with its search for ‘sociological’ laws or its formalistic rationale, we find the reflection of man’s plight in bourgeois society and of his helpless enslavement by the forces of production. “To them, their own social action”, Marx remarks, “takes the form of the action of objects which rule the producers instead of being ruled by them.” This law was expressed most clearly and coherently in the purely natural and rational laws of classical economics. Marx retorted with the demand for a historical critique of economics which resolves the totality of the reified objectivities of social and economic life into relations between men.

This is a tricky passage, but Lukacs is essentially saying that the push towards the first horn of the dilemma is the result of being in the grips of commodity fetishism. To understand how this helps resolve the dilemma, we have to say a bit about commodity fetishism.

In simplest terms, commodity fetishism involves making the specific error of mistaking relations between people for a relation between objects. But how could anyone make such a mistake?

Suppose that while at the marketplace, you and I witness the (fair) exchange of 125 bushels of corn for 1 cord of wood2 (or 3 Gameboy games for 40 Pokémon cards, or 4 dining room chairs for 5 coats, or whatever—the commodities in question don’t matter). Upon seeing see such a transaction I might wonder why those goods exchanged at the ratio of 125 to 1, and come to think that the reason rests in some particular property or set of properties of corn or wood, such that, as it were, there is something in the cord of wood itself that commands 125 bushels of corn (or vise versa) when the two commodities are brought in relation to one another.

Why I would come to think in this way is a matter we’ll address shortly, but what’s important at this point is that in thinking this way I would be making a kind of error of omission. More specifically, I would be omitting the fact that the commodities in question, like all commodities, are the result of a production process, which, in turn, is the result of certain social relations holding between people (e.g., you cutting and stacking the wood, me paying you to do it; you having to sell your labor power to me, me being in the position to purchase it, etc.). And by excluding the production process, I would likely be confusing the product of a particular social arrangement for something independent of those social relations; in even simpler terms, I would be paying attention to the wrong thing in giving an explanation.3

Why might I come to make this mistake? The short answer is that this way of looking at the world is the result of the alienation inherent in the capitalist mode of production. Under capitalism, workers sell their labor power to the factory owner for a set amount of time, during which they work on some part of the commodity production process (e.g., soldering circuit boards, spooling yarn, bending girders, etc.). Crucially, when the day is up, the workers don’t take home any of the commodities on which they labored. Instead, those commodities remain with the factory owner and are either advanced to the next step in production—for example, the soldered chips are incorporated into a bigger electronics array—or are sent to the market as finished goods for sale. In either case, when workers encounters those commodities in the market, they encounter them not as the fruit of their labor, but as objects that command a certain price on the market (a price which the worker may or not be able to afford). As such, the product appears to the workers as something set apart from them with its own autonomous and independent life—as something that they can only gain access to again should they meet it on its terms.4 Thus, it is the very conditions necessitated by the commodity production process, and specifically the encounter of commodities at the market that encourages commodity fetishism and, consequently, the error that it entails.

Much more can be said about commodity fetishism, and much more should be said before one takes it on board, but this is enough to get us through this thorny section.5

Or at least enough to get through Lukacs’ explanation of how Marx dissolves the dilemma. Simply put, Lukacs is saying that the compulsion to find sociological laws of nature is a result of commodity fetishism, which is itself a direct result of the conditions of (commodity) production.6 Because academics and economists are as much in the grips of fetishism as anyone else, they invert the normal order of things. Instead of seeing commodities as the end product of a certain process that exists due to the enforcement of certain contingent social relations, they come to think of those commodities as constituting the beginning of a different process that ends in an understanding of the natural laws that dictate their behavior.7

The bigger point here is that commodity fetishism is not limited to how we think about commodities, but rather, because of the central role that commodity production has in how society is reproduced, its conditions affects (infects) our way of thinking about all other aspects of life, including the way we do science, philosophy, and history. Once we understand that this compulsion is a reflection of our particular (current) state and not a requirement for grasping the truth, we can also see that we are not forced into the first “universalist” horn of the dilemma. There’s no need to look for universalist laws of commodity circulation because the very compulsion that pushes us in that direction is premised on a false understanding of the world.8

So much for the first horn. But what about the second, “individualist” horn that transforms history “into the irrational rule of blind forces?” It, too, is exposed as illusory in the same fashion:

By reducing the objectivity of the social institutions so hostile to man to relations between men, Marx also does away with the false implications of the irrationalist and individualist principle, i.e., the other side of the dilemma. For to eliminate the objectivity attributed both to social institutions inimical to man and to their historical evolution means the restoration of this objectivity to their underlying basis, to the relations between men; it does not involve the elimination of laws and objectivity independent of the will of man and in particular the wills and thoughts of individual men. It simply means that this objectivity is the self-objectification of human society at a particular stage in its development; its laws hold good only within the framework of the historical context which produced them and which is in turn determined by them.

This is another difficult passage, but, thankfully, we’re already equipped to deal with it based on what’s already come before.

Recall that when confronted with the dilemma in its original form, the implication appeared to be that if history does not proceed along the lines of necessary and eternal laws of nature, then in the absence of such laws, it must proceed along the lines of individual wills. However, we now see that the absence of fixed natural laws governing social relations does not mean that what governs them must be the thoughts and wills of individuals. We are not forced to move from the realm of the eternal and universal (mathematical?) explanation directly to the realm of the particular and individualistic (unsystematic?) explanation. Rather, we can occupy a third space in which we can identify perfectly objective explanations of historical development, but which only hold as such within a particular historical context. We do this by subjecting to a critical analysis the logic of the social relations that hold within that context, and, in particular, the social relations that comprise the reproduction of society.

Do such explanations have the status of laws of nature? No—they don’t hold everywhere at all times and in all contexts. Does that mean that they’re therefore entirely subjective and grounded in the wills and thoughts of individuals? No—they are perfectly objective within a specific historical context.

But does accepting this third position mean that the ideas and actions of the individual do not make any difference to the process of history? Lukacs gives a puzzling answer, the untangling of which will take us through the rest of this entry:

[historical materialism] does not deny that men perform their historical deeds themselves and that they do so consciously. But as Engels emphasizes in a letter to Mehring, this consciousness is false. However, the dialectical method does not permit us simply to proclaim the ‘falseness’ of this consciousness and to persist in an inflexible confrontation of true and false. On the contrary, it requires us to investigate this ‘false consciousness’ concretely as an aspect of historical totality and as a stage in the historical process.

So, people do act and they act consciously, but their consciousness is false. This much is clear, and at this point, one naturally anticipates that Lukacs would explain what it means for a consciousness to be false. Instead, he tells us that we must analyze the falseness of that consciousness in the specific concrete moment, which, in turn, involves analyzing its relation to the entire process of history.

In one respect, this is fine—what he’s telling us is that we can’t say that the consciousness that Napoleon had when he willingly and consciously turned his troops towards Moscow was false tout court, but can only determine and analyze its falseness withing the totality of historical development. Again, this is fine, but the problem is that we don’t yet know what it means for Napoleon’s consciousness to be false within or without the concrete context in which calling it false is appropriate. It’s like telling someone “remember, the gleeba can only operate on state sanctioned roads” without telling you what a ‘gleeba’ is. It’s fine to know that it only operates on state roads, but that matters very little if you don’t know what it is.

Compounding our frustration, Lukacs continues not by giving us an explanation of false consciousness, but of ‘concrete analysis’, which itself is illustrated negatively by way of telling us where bourgeois historians go wrong. The issue is one of scope: bourgeois historians can only conceive of the limits of concrete totality as ending at the level of society as it exists within the current system of production. We’ve already seen what this looks like when we looked at the Adam Smith passage in the last section—because our society operates on the basis of commodity production for the purpose of exchange, therefore, all society everywhere must have on that basis, or, at the very least, must have anticipated the present moment in some embryonic state. Such historians simply see their present society as reflected back at them through the ages rather and fail to see, on the one hand, the actual development of all society through the ages, and, on the other hand, the need to explain that development.

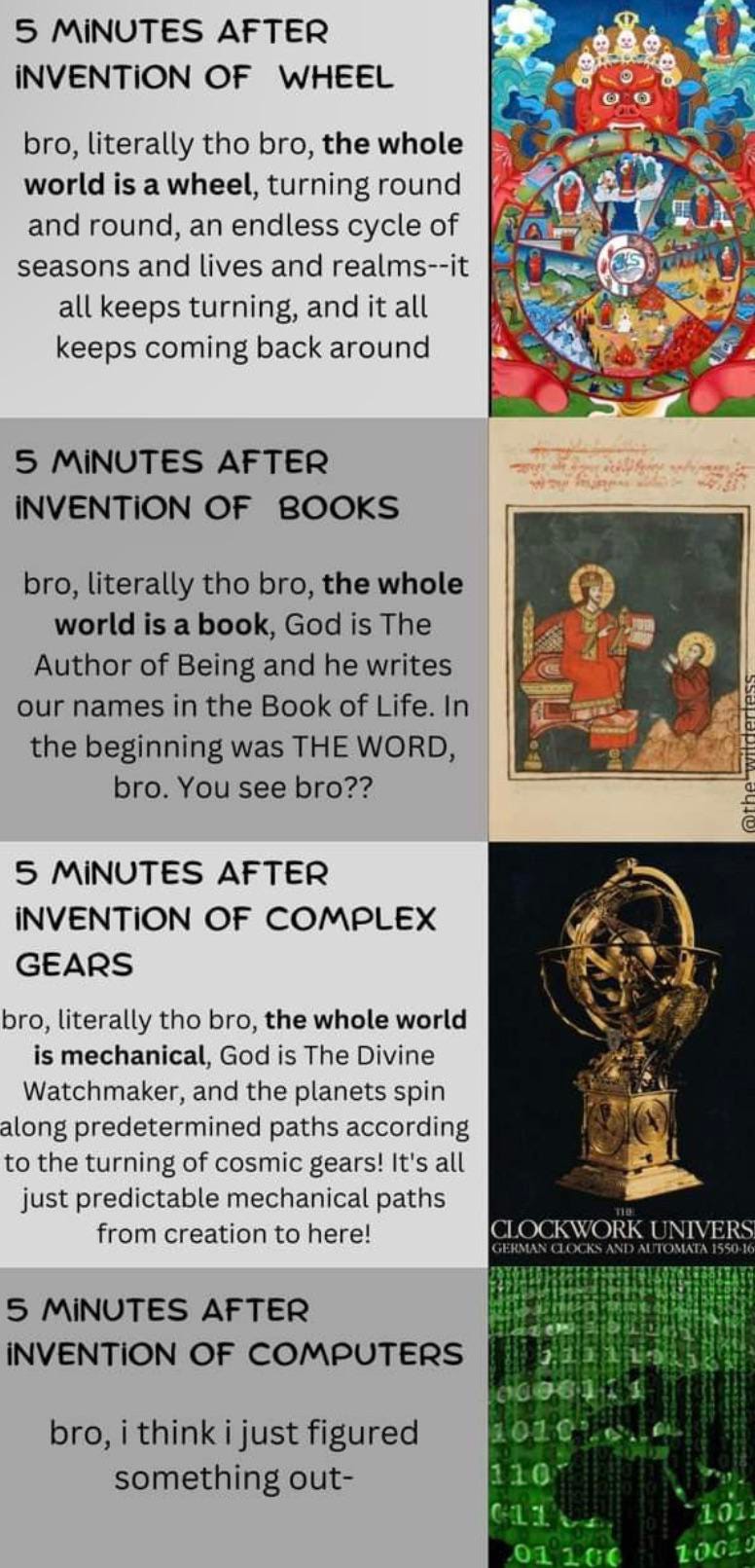

In a way they operate a bit like the characters in this meme that I shamelessly stole, but which I think about more than I care to admit

Setting aside the question of whether any of the bros is correct about their particular era, we can see the two kinds of mistakes at play: first, each only reaches the limits of his9 own era and mistakes it as speaking for all; and second, none addresses the transition between the vastly different eras. Each explanation, thus, remains partial at best and false at worst.

If what has been described is not concrete analysis, then what is?

Concrete analysis means then: the relation to society as a whole.

Thanks, Lukacs…that’s, uh, really helpful. Let’s keep going

For only when this relation is established does the consciousness of their existence that men have at any given time emerge in all its essential characteristics. It appears, on the one hand, as something which is subjectively justified in the social and historical situation, as something which can and should be understood, i.e., as ‘right’. At the same time, objectively, it by-passes the essence of the evolution of society and fails to pinpoint it and express it adequately. That is to say, objectively, it appears as a ‘false consciousness’. On the other hand, we may see the same consciousness as something which fails subjectively to reach its self-appointed goals, while furthering and realizing the objective aims of society of which it is ignorant and which it did not choose.

At last, we have a definition of ‘false consciousness’, but it’s one that Lukacs is going to make us work for.

A couple of things are worth pointing out to help us: first, regardless of whether it is false or not, there’s a “subjective” element to any particular consciousness that makes it appear as normal and justified in its particular context. In other words, false consciousness doesn’t feel or look any different from “true” consciousness. “From the inside,” as it were, false consciousness appears the same way as, well, whatever your consciousness is now. The same is true for any previous time period—the right of kings over their subjects was seen as justified and appropriate under feudalism; of slavery under the rule of antiquity; and, of course, of private property of the means of production in our present moment.10 False consciousness doesn’t make itself apparent as such.

Second, the falseness of a false consciousness becomes apparent only in contrast to or against the background of its objective character. We know the character of the class’s consciousness only when we figure out what aims and goals its actually aiming for, and, crucially, what aims and goals it has in its total relation to society and not merely in the present moment.

This is a bit tricky, so let’s try to flesh it out.

Consider, for example, how this might be possible on the scale of individuals. Suppose that we have before us a heartbroken lover who, despite the conscious and intentional desire to move on after a break up, finds himself repeatedly driving by his former lover’s workplace, walking down the street where the two shared an apartment, and so on. From the inside, this person may feel like his behavior has a clear and rational explanation (“Driving by their work is the fastest way to get from my house to my parents’!”, or “Maple Street has the most gorgeous parks and it’s important to get exercise!”, and so on). And that might very well be correct—that is, driving past their former lover’s work may really be the fastest way to get from one place to another; it is important to get exercise—but when setting those rational explanations in context, it is also apparent that the behaviors in question nevertheless point to a further aim that is achieved in performing them: namely, running into the ex-lover.

We say of a person like this that he is operating with a false consciousness. But, crucially, we detect and recognize this consciousness as false within the broader context of what actually happens (and has happened in the past), and not simply by virtue of the content of the lover’s thoughts. It is only in the context of the heartbreak and in light of the fact that the former lover works at this place that the falseness of the consciousness is made apparent. If there were no heartbreak, or if the former lover worked somewhere else, driving down the street in question would not constitute an example of false consciousness (as, presumably, it doesn’t when someone else drives down that street). In other words, it is by contrasting the heartbroken man’s actions with what actions he would perform otherwise that we see them as aiming at something other than what he thinks he does.11

To round out the analogy, as with the individual, the falseness of the class consciousness is not something that is read off by looking at what the class “thinks” it is doing at some given moment, but rather by examining its “actions” in light of an analysis that establishes the objective aims of society as a whole.12 In other words, we do it by providing what Lukacs calls a ‘concrete analysis’. It is by supplying this concrete analysis—by tracing out of the dialectical developments (i.e., the dynamic back-and-forth interactions) between the classes as they engage in class warfare in relation to all of society—that we are able to contrast the particular consciousness of the class as we find it presently.13

More specifically, what this means is that in performing a concrete analysis, we are meant to establish the position that the class would have given the overall development of society. Thus, Lukacs says:

By relating consciousness to the whole of society it becomes possible to infer the thoughts and feelings which men would have in a particular situation if they were able to assess both it and the interests arising from it in their impact on immediate action and on the whole structure of society. That is to say, it would be possible to infer the thoughts and feelings appropriate to their objective situation.

Consider another analogy with waging warfare. In assessing whether a general is thinking “correctly” when engaging in a particular battle, we would want to consider not just what the general is thinking in the moment, but what a general taking such a battle would think given the development of the war. Does taking the battle further the aims of the war (rather than, say, the career of the general)? Has the last battle depleted the brigades’ supplies? Does the opposing general have air support? And so on. By learning the answers to these questions, we would be able to establish what a general would do if he were able to, as Lukacs says, both their particular situation (the battle in question, here and now) and its impact on the war. So with determining the consciousness of a class.

But here’s where it gets a little weird:

Now class consciousness consists in fact of the appropriate and rational reactions ‘imputed’ [zugerechnet] to a particular typical position in the process of production.

Note, the consciousness of a class is not the aggregate (“neither the sum nor the average of what is thought or felt by the single individuals who make up the class”) of individual thoughts or wills, but what is imputed as appropriate given the class’s position. Thus, the consciousness of the actual working class in the United States, for example, is what would be appropriate and rational for its members to do in light of, say, the decimation of the trade unions, the privatization of pubic resources, the destruction of the social wage, and so on. Crucially, this would be its class consciousness even if no member of the actual working class had any of those positions.

Is this the case? We’ll pick up here in the next section.

You might be wondering if this is accurate. I looked it up—it’s roughly correct.

At the risk of belaboring the point, we can draw a useful analogy in the realm of religion. Originally, a ‘fetish’ just referred to any small, inanimate object worshipped because of the (supposed) magical powers that it commands. Strictly speaking, what lies before us when in the presence of a fetish is a piece of wood, cut from a tree or collected from the ground, carved by some sharp instrument, and painted or decorated with jewels or shells. Carved pieces of wood cannot control weather patterns, allow for communion with the dead, or command the living to do their bidding. Wood simply doesn’t have such powers, nor can it acquire them in the process of being shaped or molded in any way. Of course, (very many) people may believe that the idol can do all this, thank the idol when the rains come in, grip it firmly in trying to communicate with the dead, and be convinced unto death that they must do what the idol instructs. But on a strict materialist assumption, such people are mistaken. They have confused an object produced by people for something that stands above and beyond that process of production and which has its own inherent powers. The same mistake is made by people who think that, for instance, the iPhone has an inherent value of its own (perhaps because of its beautiful sleek design, fast processing power, and beautiful casing!) which makes it fetch $1000.

This is pretty much a paraphrase from my other piece on alienation. I don’t know if it counts as self-plagiarism, but I’m working on filing a court case regardless.

For example, is commodity fetishism a phenomenological condition? Is it a cognitive or psychological one? Is it enough to understand what commodity fetishism involves in order to avoid it? Or does it involve a cultivation of a certain sort of intellectual virtue? (I don’t know!)

I flag this because this link to the production process is what keeps the explanation a materialist one. It’s not the case that we just have gotten a bad batch of ideas that have duped us into fetishism. If that were the case, it would be possible to just get a new, better set of ideas and preserve the production process as it is. By making fetishism a direct result of the very conditions of production, Marx and Lukacs implicitly argue that this cannot be done—in order to get rid of fetishism fully, we have to alter the social relations. This, of course, fits in rather nicely with the famous 11th thesis on Feurbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.”

What’s the alternative? While in the grips of fetishism, we take the commodity as the starting point of main unit of analysis, and (foolishly) search for ways to fit everything around the natural laws that we assume they must conform to; by contrast, when free of fetishism, society and our needs form the starting point and main unit of analysis, and we are tasked with figuring out a way to organize ourselves and our relations so as to meet those needs. Crucially, this is not a utopian vision of what could be possible, but deeply rooted in the technological and industrial possibilities afforded by the industrial revolution. Another way of saying this is that industrialization unleashed incredibly productive powers (powers which Marx praises!) with which the needs of everyone could be met but which are not because of the specific social relations of capitalism. For example, we have, for a very long time now, been able to produce enough food to feed the entire world—I think Elon Musk alone has enough private wealth to make this happen—but what prevents this from actually happening is that the product of the labor of so many workers is guaranteed as the private property of the farm corporation, to do whatever they want with it with the backing of the state and its monopoly on violence.

In slightly more technical terms, Lukacs is offering us an error theory.

Ladies can be bros too. But these are obviously male bros.

Of course, this justificatory process involves all sorts of institutions whose purpose is to explain and rationalize the status quo. We have those too.

Note, none of this means that the man doesn’t act consciously or that the thoughts that he has are irrelevant.

A careful reader might have noticed an apparent slip. In the class context we look at the history between classes to establish the objective background of the aims of society—in the individual case, we look at the history of the individual to establish the objective background of his aims. There doesn’t seem to be an analogue to society in the case of the individual. I think that’s reasonable, but that it’s addressed with minimal violence by saying that we look at the individual’s social history to establish his goals. That is, we look at the totality of the individual’s social life, which, of course, includes the history of the previous relationship. I’m afraid that’s the best I can do here.

Lukacs’ line of argument assumes that there is a determinate movement—an objective essence to society—that can be expressed and understood by tracing the dialectical method of historical materialism, and, in particular, by uncovering the dynamics of the struggle between the laboring and non-laboring classes. In one sense, this shouldn’t be surprising since this is simply a statement of the method that Marx introduced and that Lukacs tells us allows us to dismantle the dilemma that we’ve been focusing. So as not to repeat myself too much, on the one hand, the method allows you to avoid the aesthetic individualism that constitutes one horn of the dilemma (history isn’t just the chaotic actions of individuals—it operates according to the dialectic of the class struggle), and, on the other hand, it allows you to avoid the universal formalism that constitutes the other horn (the dialectic of the class struggle isn’t the same everywhere and for all times, but takes a particular character in particular settings based on the relations of production that hold).